The purpose and role of the budget can best be explained in the context of strategic planning. You will save yourself much time and stress during budgeting by building off pieces of planning that have already been done.

There are many ways these pieces, and the pieces developed during budgeting, can fit together. I’ve heard many times from managers how they hate having to go through more than one round of budgeting.

It’s like being stuck in traffic and being mad at everyone else for clogging up the road. We are all usually part of the problem. We all want more than capacity allows. In this case, we all want more resources than budget capacity allows.

Human dysfunction aside, budgeting is inherently iterative. It takes time to find the best compromise mix of strategies. The right balance of clarity of expectations and aggressiveness of targets can lead to effective budgeting.

Overview of Strategic Planning

Strategic planning programs share very similar components. However, they often use different words to describe these components. Here is a summary of how I name and define the components and how they fit together.

My main goal is not to give a comprehensive background in strategic planning but to show you how budgeting fits into planning.

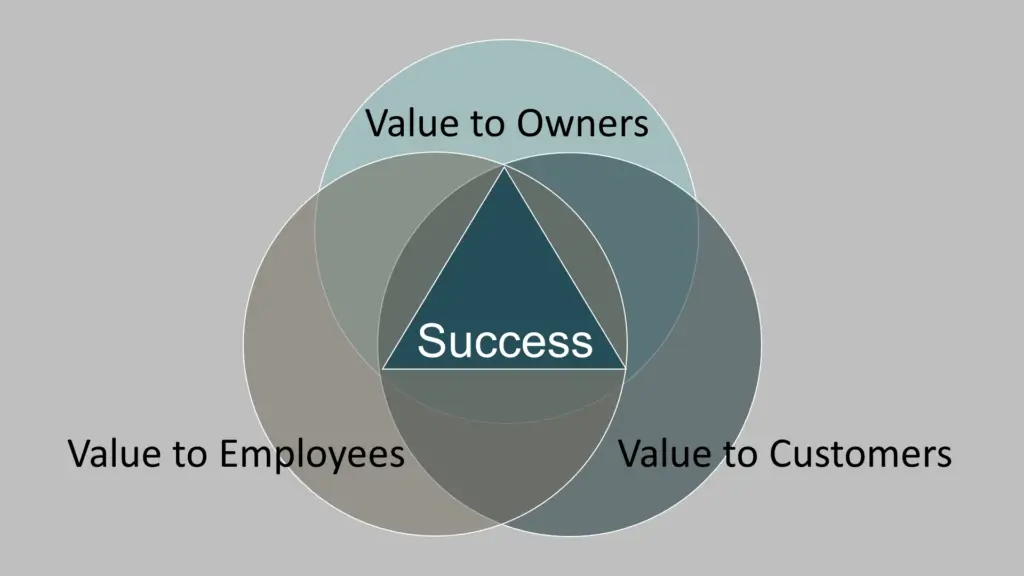

It starts with what the owners value. The purpose of a company is to serve the values of the owners.

I’ll pause here to provide context for what I mean by this. As an owner, you must give value to receive value. The owners of a company only receive value when they provide value to customers and employees. Business success lies where everyone gives and receives value.

The purpose of your business leads to the vision for your business. Vision is your description of what your company will look like and do in the future. It answers the question, “Where are you going?”

That leads to your company’s mission. The mission is how the company will achieve its vision.

I know that the definitions of mission and vision are often used interchangeably or in different ways. I use the definitions only for clarity in the context of this strategic planning process. Regardless of your definitions, every company needs a plan for where it’s going and how it’s going to get there.

The bottom half of the pyramid provides a detailed plan for answering the big questions of purpose, mission, and vision. You answer the following questions in successive stages of increasing detail:

● What needs to be done?

● Who will do it?

● When will it get done?

You start by setting your company’s priorities for the next three years. You then define what goals you’ll accomplish next year. Your annual goals are broken down into quarterly objectives. Finally, you list the projects and tasks needed to achieve those objectives.

Quarterly objectives may be set using a system like objectives and key results. Tasks can be managed by a wide variety of project planning systems.

Assumptions and Strategic Planning

In strategic planning, you decide your assumptions and the actions based on those assumptions. Assumptions you make in strategic planning are needed to set key budgeting assumptions. Some examples are:

- Economic conditions determine the size of the market and customers’ ability to pay. These impact sales.

- New products or services you think competitors will release will change what you prioritize for release.

- You may see opportunities to raise prices.

- Inflation can cause big increases in funding and staffing costs.

Assumptions are crucial to your strategy. You must change your strategy when the assumptions of your strategy are no longer valid. Many KPIs monitor the performance of strategy implementation. You must also monitor metrics that measure the validity of your strategic assumptions.

Another way to prepare for budgeting is to ask, “What decisions will I need to make in the budget?” Budgeting is a form of analysis, and the purpose of analysis is to make good decisions.

Build a list of those questions and data to help answer those questions throughout the year. Strategic planning is more relevant when it provides information for your budget questions. Your budget questions also inform what you should research in the economy or with your competitors.

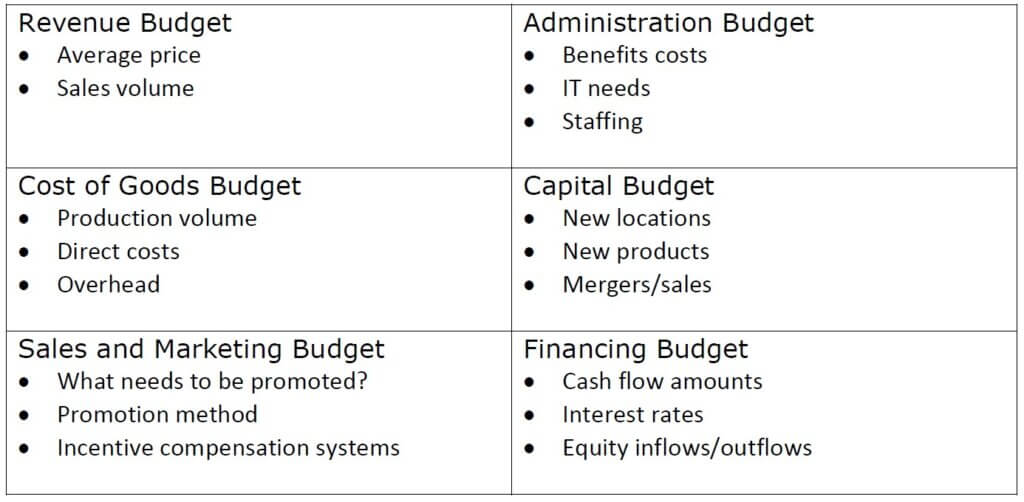

Below is a list of the major sections of the budget and their key assumptions, variables, or components.

You may have strategies and ideas that will likely need to be budgeted for. In the busyness of today, it’s tempting to think you’ll push that analysis and decision until the budgeting process. The problem is that many decisions get delayed like that and then get rushed in the crush of budgeting season.

You can build the budget for some items (e.g., new locations, new products, new IT) with the best information you have months before budget season. You can then tighten down those assumptions in the budgeting process.

How Budgeting Fits with Strategic Planning

Budgeting translates longer-term priorities (i.e., three-year strategic priorities) into one-year goals. The three-year strategic priorities focus on identifying the long-term strategies that will create value. It entails lots of scenario analysis and forecasting to assess profitability. At this stage, you are not prioritizing them or scheduling their implementation. You may create broad implementation plans but not detailed project plans with deadlines, detailed costs, etc.

Budgeting is part of the process of defining your one-year goals. You decide which three-year priorities you will do in the next year and which will be in future years. Some priorities are multi-year plans, so you’re deciding which parts of those plans will occur in the next year.

Once again, it’s an iterative process. You’ll identify an initial set of projects for implementation in the next year. As you put the budget together, you’ll discover whether you have the time and money to implement them. You may need to push some projects into future years; you may find you can add more projects.

Once you decide which projects are added, you plan them out in more operational and financial detail. That financial detail is layered into the budget.

The top portion of the planning pyramid defines the company’s long-term strategies. Potential strategies are prioritized by when they need to be implemented and their effectiveness.

All that planning is crucially important to the efficiency and effectiveness of budgeting. If you try to create a budget, especially with a group of people, you will be forced to go back and answer these strategic planning questions.

Strategic planning is also not a linear process that occurs once a year or once every few years. The business environment is constantly changing. These changes:

- Modify the accuracy of the plan’s assumptions

- Add clarity to the probability of success of strategies

- Introduce new challenges and opportunities

Significant updates in the business environment force us to update past strategic analyses or create new ones.

It might not shock you to learn that I’m naturally analytical. By habit, I fire up a workbook or dive into data analysis software. Others may tweak models they carry in their minds. Regardless of the method, strategic plans evolve.

Budgeting forces these analyses, strategies, and conceptual models into a coherent and integrated whole. It puts money where our mouths and minds are. I say this in the plural because the group must come to a consensus budget from their various perspectives of the business. This is how a budget can enhance clarity, coordination, and communication.

One way to think about going from strategy to a budget is by asking three questions:

- Strategy – What will we do to create value?

- One-year goals – What will we do next year to create that value?

- Budget – What are the financial implications of our one-year goals?

Preparing Analysis Before Budget Season

Doing planning and analysis outside of the budgeting process helps us survive budget season. Strategic planning is usually done with a fairly small group of people. Ad hoc analysis also involves smaller groups of people. Budgeting likely takes many people in the company. They may be asked to do more financial analysis than they do any other time of the year.

You can only fit a limited number of decisions in the window of time you set for budgeting. Good strategic planning and ad hoc analysis create large blocks of strategic analysis from which to build the budget. This frees up more time for all the other analyses inherent in the budget process.

When I was in public accounting, the busy season was the start of the year when audits and tax returns for the past year needed to be completed. In industry, it was budget season. This was the busiest time for financial analysis in the year. The Finance and Accounting departments were completely consumed by it. It also took up lots of time for managers throughout the company. It’s not just time but energy. Tough decisions are made in difficult meetings.

In public accounting, the goal is to move as much work as possible from busy season to interim work earlier in the year. The goal is the same in budgeting.

What can you move earlier in the year? One way to decide is to ask, as early as possible, what decisions need to be made to compile the budget. Then ask, what analysis needs to be done to make those decisions? What is the earliest we can do most of that analysis?

Take this one step further back and ask, what info will I need to do that analysis? Do I have that information, or do I need to develop it? Examples of information you may need include:

- Variable and marginal costs

- Marginal revenue

- Capacity analysis and costs to increase capacity

Budgets, Forecasts, and Projections

There is a technical difference between a forecast and a projection. According to the AICPA (American Institute of Certified Public Accountants):

- A forecast “is based on the responsible party’s assumptions reflecting the conditions it expects to exist and the course of action it expects to take.”

- A projection “is sometimes prepared to present one or more hypothetical courses of action for evaluation.”

In other words, we are making projections when we’re looking at potential scenarios. Once we decide on a most likely projection, we have a forecast. A budget is usually a forecast that is extensively developed and documented.

Budgets usually don’t change for the time they analyze (e.g., annually). Forecasts are often updated (e.g., monthly or quarterly). Budgets set financial targets and key performance indicators (KPIs). Forecasts are often used to see if those targets will be met.

These three types of analysis can inform each other. While preparing for this course, I read one article that said to start with your budget and then develop forecasts. Another article said your budget should be based on your forecasts. So, the order isn’t always agreed upon, but people do agree that budgets and forecasts inform each other.

Ad hoc projections of specific investments or scenarios can be incorporated into a budget or forecast. The budget is the starting point for projections used in scenario and sensitivity analysis. Forecasts may lead to budgets; budgets may be the foundation for future forecasting.

Projections and forecasts are like the Ghost of Christmas Future in the story A Christmas Carol. The ghost shows Ebenezer Scrooge’s bleak future based on the current trajectory of his life. His choice is to stay on that path or make big changes for a better future.

Projections and forecasts start with an extrapolation of the company’s current trajectory. That extrapolation is the “Ghost of Net Income Future.” It tells managers what will happen if they don’t change their ways. When that future is bad, managers must wake up like Scrooge and greatly change their actions. Those changes are the “courses of actions it expects to take” in forecasts and budgets.

Key Assumptions and Limits

It would be nice to start the budget at one point (e.g., sales) and then linearly coordinate off of that. There are usually too many dependencies in a business to do that. Once sales are set, the sales department will ask for staffing, advertising, pricing levels, technology support, etc.

Those costs may make the resulting profit unacceptably low. This starts another iteration of sales and costs to reach an acceptable profit target. Thus, budgeting is iterative.

On the other hand, budgeting cannot start from a blank slate. There are minimum acceptable levels and constraints. They may be unknown and unspoken. The planning process should define the nature and targets of key assumptions. The amounts can be a single number or a range of numbers. Examples of assumptions would be targets for:

- Net income

- Cash distributions to owners

- Growth rates

- Revenue

A budget allows capacity optimization across the company for a narrow range of sales/production targets. Without this, there are too many options for managers to budget for. Wide ranges of assumptions are good for projections, scenario analysis, and sensitivity. Budgets must have a narrow set of assumptions for which a detailed forecast is developed.

There is also an iterative relationship between key performance indicators (KPIs) and the budget. KPI development occurs both before creating a budget and after the budget. Some KPIs are developed before the budget as the assumptions of the budget that I just described. The targets for these KPIs are likely ranges at this point of planning. The budget would then set:

- The exact target for a KPI target range that was an assumption.

- The target for KPIs that weren’t assumptions or limits for the budget.

Other key assumptions would include major strategies the company is planning to implement in the budget year. These might include:

- New or closed locations

- Pricing strategies

- Inventory levels

- Product changes

- Advertising and marketing strategies

- Major staffing changes

Some of these strategies will be known at the start of the budget process. Strategies can change, though, because:

- The company adds new strategies because it finds capacity for them.

- New strategies may be needed to get early versions of the budget to an acceptable final version.

- The company takes strategies out of the budget because there isn’t capacity for them.

In other words, company strategies are iterative. I may have mentioned earlier that budgeting is inherently iterative.

Those leading the budget process have to find the right balance of assumptions and limits to provide to those preparing parts of the budget.

- Too few assumptions and too little guidance will cause managers to beg for clarity. Early budget versions won’t fit together well. One department’s budget will be completely out of sync with another department. Future iterations will focus on trying to coordinate the conflicting parts of the budget.

- Too many assumptions or limits will drive many budget iterations before satisfying them all. If you don’t satisfy them all, you may die trying. It can force creativity or consume massive amounts of analysis time trying to solve the impossible. Some assumptions may need to be adjusted.

Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up

I opened this article by explaining a planning pyramid from top to bottom. This does not mean planning starts from the top of the company and then rolls out down the company. Planning and budgeting can occur both top-down and bottom-up.

- Top-Down: Directives and information can flow down from the top of the organization. Lower levels of the company build budgets within tight but vertically aligned boundaries.

- Bottom-Up: Information, ideas, and potential strategies rise up from across the organization. Company leaders spend more time coordinating them into a cohesive strategy that fits company constraints.

These are simplifications. There are ways to make both ways work better than described above. Most companies do a combination of the two methods.

To get step-by-step guidance on how to improve your business’s budget, check out my Better Budgeting course.

.

For more info, check out these topics pages: