I like to say that the deals are in the downturns. Here are steps to take before a recession and what to do during the recession. These can make your company stronger to capture the opportunities I’ll list in the last part of this article.

Before the Recession

Scenario Planning

The first step is to model the potential impacts and implications of a recession on your business. A simple way that many businesses do this is by starting with their budget and then creating a “best case” and “worst case” scenario from that. These two scenarios tend not to deviate enough from the base case. In other words, the potential best case is better than you think, and the worst case is worse than you think. Thus, push the assumptions to more extremes that you may initially set to widen your view of the full range of potential outcomes.

Another other option is sensitivity testing. Sensitivity testing involves varying the amounts of one assumption at a time to identify the magnitude of impact that assumption could have on outcomes. You quickly find out the key drivers of your success. This provides clarity and focus.

Break-even analysis can be done to solve the problem in the opposite direction of sensitivity analysis. In other words, you set earnings to zero (or some other minimum acceptable number) and then back into the levels of assumptions that would cause this. You can then ask yourself how likely it is for the assumption to actually hit that break-even level. The probability may be high enough that you decide to implement steps to reduce that probability or mitigate its impact.

A recession usually causes more than one of your scenario assumptions to be negatively impacted. As the saying goes, “When it rains, it pours.” Stress testing allows you to model this. When I worked in banks, I would create stress scenarios with varying degrees of stress and due to different causes. For example, one scenario would model the impact and mitigation of the Federal Reserve payment system being inoperative. Another scenario was a large decrease in deposits. Stress scenarios can push you to identify threats and identify dependencies that would cause one thing to negatively impact another thing.

Behavioral finance studies have found that we tend to extrapolate the recent past into the future. If the recent past has been good, we are more likely to project positive future trends. If the recent past has been bad, we project a darker future. This can blind us to the potential of good times being followed by a recession or a recession’s end, leading to the next economic expansion. This blindness causes us to be unprepared for both challenges and opportunities. Optimizing your company for one scenario (i.e., your budget) can leave you vulnerable to unacceptable risk in an uncertain world.

The questions financial leaders should ask themselves when reviewing these scenarios are:

- What are the probabilities of the negative outcomes?

- Should we do something to reduce the impact to a more acceptable level?

- What are the options for mitigating these risks?

Scenario analysis during the good times gives you time to prepare for the bad times. I’ll also show in a later lesson that you want to position yourself for opportunities in a downturn. This can all be summarized by three quotes by great thinkers:

- “Failure to prepare is preparing to fail.” – Benjamin Franklin

- “Luck happens when preparation meets opportunity.” – Seneca

- “Only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.” – Warren Buffett

Cash Flow

I’ve already mentioned the importance of cash, so it’s no surprise that improving liquidity is a crucial step for a company before a recession. Cash reserves serve two purposes during a recession. Defensively, they may be the only way to fund operations for some companies. Other companies can use the cash to take advantage of opportunities, such as buying weaker companies.

The strongest form of liquidity is a cash reserve equal to at least three months of expenses. I remember saying this to a group of small businesses I once talked with and wondering whether this buffer amount may be too conservative. A month later, COVID hit. Many businesses were shut for weeks with lower volumes for months. Those with three months of savings fared much better.

Another form of liquidity is a line of credit. Some companies think they don’t need this during the good times. Banks usually charge a commitment fee of around 1% for the commitment amount of the line, so there is a cost for a line even when you don’t use it. However, a line might provide funds when cash balances would otherwise go to zero in hard times. Companies that have a comfortable margin of liquidity can focus on creating profits, not trying to maintain a minimum level of cash flow. A line is a source of funds when a company needs cash quickly to capture an opportunity.

There are two reasons to get a line of credit during good economic times:

- It takes time to get approved for a line.

- A company may be too weak to qualify for a line in bad times.

Related to getting a line is building a relationship with your banker. I’ve sat on loan approval committees. I had to approve pricing for large fixed-rate loans at one financial institution. I can tell you from experience that loan officers advocate for their customers. It could be said that they are fighting for their commission, but these bankers truly care about their customers. Loan officers are also a good source of advice. They’ve seen companies make good and bad financial decisions. That guidance and advocacy may be important when a company is struggling and at risk of losing or not getting a loan.

Once again, it takes time to get a loan. Part of this time is educating the loan officer about the company. Gathering required documents takes time. Many times, a company comes to a loan officer but doesn’t currently qualify for a loan. The lender can provide advice on what the company can do to improve its financial strength to become credit-worthy.

Leveraged companies are under more liquidity pressure during a recession. There are good reasons that companies take on leverage. An excellent opportunity to buy assets or to acquire a company may arise that requires leverage. However, a company doesn’t want to be caught over-leveraged during hard economic times. Companies should make efforts to reduce debt levels during good times. This may be via an equity infusion. A company can also pay down debt instead of investing in lower net present value (NPV) projects. A third option is to extend debt maturities to reduce monthly principal and interest (P&I) debt service payments and to avoid having balloon payments come due during a potential near-term recession.

For closely held small and mid-size companies, the company should assess the strength of the owners’ balance sheets and cash flow needs. Owners who can provide cash when needed to a company are a source of strength for the business. Other owners are a liability to a company, constantly requiring cash from the company for their personal needs. These owners can’t rely on those cash flows when their company is weakened by a recession. That owner’s personal financial weakness may also cause the demise of their company during hard times. Many banks require personal guarantees from small business owners. Poor personal finances thus also limit the ability of the company to get bank funding.

Cost and Revenue Strategies

A company may be using everything it has to keep up with demand during the good times. All resources are focused on production and volume. This is a good problem, but it also can create other problems.

A company buried by current operations may lose sight of strategy. One strategy is building relationships with potential merger candidates. A relationship you build during the good times means you are the first person the candidate calls when they want to sell assets, sell their company, or need equity in the hard times. Identify what you want to buy when things get cheap. The deals are in the downturns.

Another strategic move may be diversification. Like personal financial planning, businesses with diverse cash flow streams are less susceptible to a decrease in any one stream. Here are some types of diversification:

- Customer Diversification: A company with one dominant customer has put their company’s fate in the hands of that customer. Both will go down together if the dominant company struggles in a downturn. Good economic times may provide opportunities to reduce reliance on one customer and increase sales to others.

- Product and Service Diversification: A recession may impact one part of an industry more than another. For example, people may buy fewer cars and instead spend more on maintaining their current car. The same goes for office machinery. Low cash flow or profits from one product might be offset by countercyclical increased cash flow from another product.

- Version Diversification: A common tactic during recessions is for companies to offer a lower-priced version of their products. This may be under the company’s brand or under a new brand. For example, wineries will sometimes come out with a second label (i.e., brand) to sell excess inventory at a lower price without hurting the sales and image of their regular brand. Once again, the preparation for this takes time. There are many items that can be readied before economic stress occurs.

Another area that suffers is cost management. It’s easy to let costs build during good times. You’re just trying to keep up with business. However, they are constantly leaking profits. Also, investing in efficiency may mean a drop in cash flow before the savings allow improved cash flow. You may not be able to deal with lower cash flow during the recession, meaning you are stuck with inefficiency. Good economic times with high cash flow may be a better time to make efficiency investments.

Companies must also decide the scalability of their costs. Companies with variable costs may be less profitable during good times but have better cash flow in downturns. Fixed versus variable cost decisions include:

- Buying vs leasing facilities

- Hiring employees vs using contractors

- Bringing processes in-house vs outsourcing them

Inventory management strategies also help companies prepare for recessions. Two different strategies apply to different types of companies. Some companies are very susceptible to getting stuck with large amounts of inventory during a downturn. This may come with storage and spoilage costs. These companies should focus on reducing on-hand inventory.

Other companies may be very susceptible to supply chain disruptions. These companies should diversify their supply chain. Supply chain disruptions may be the catalyst for a recession. Examples include trade wars or military wars. I have a friend who sells electrical infrastructure. Their supply chain was severely disrupted by COVID. They were starting to recover from that when they began to struggle to get some printed circuit boards. These boards were coated with a substance that comes from Ukraine, which was at war with Russia.

Another (potentially literal) option is a hedge. When I worked at banks, we sometimes had interest rate swaps to protect us from unfavorable interest rate movements. I worked at an ag bank where farmers locked in crop pricing well before harvest. A business may hedge against currency risk. Some businesses buy options for goods from suppliers rather than committing to buying goods on contracts.

I’ve talked about more formal financial hedges so far. Businesses may also use informal hedges in their strategy so they aren’t completely committed to one course of action that exposes them to high expenses when the economy moves another way. One example I showed earlier was balancing cost scalability across a range of sales against profit maximization at a high sales volume.

How confident are you that tomorrow will be as good as yesterday? This is not a black-and-white or yes/no question. Are you 100% confident? 80% confident? 50% confident? At what percentage do you put hedges in place for downside risk?

This brings us full circle back to scenarios. The scenario planning I mentioned at the beginning of this lesson helps you think through how likely a recession might be and the company’s magnitude of downside risk.

Monitoring key performance indicators (KPIs) and other metrics also brings us full circle back to sensitivity analysis. This analysis shows a company’s key assumptions to successful outcomes from its strategy. These assumptions, along with others, may be incorporated into KPIs and metrics to monitor less intensely. A potential leading KPI of a downturn is a falling sales pipeline. You could also monitor leading national economic indicators to monitor for a weakening economy.

During the Recession

Cash Conversion Cycle Management

We start once again with cash flow management. Recessions hurt cash flow in multiple ways. Sales decrease, collection times increase, and cash may be trapped in high inventory levels.

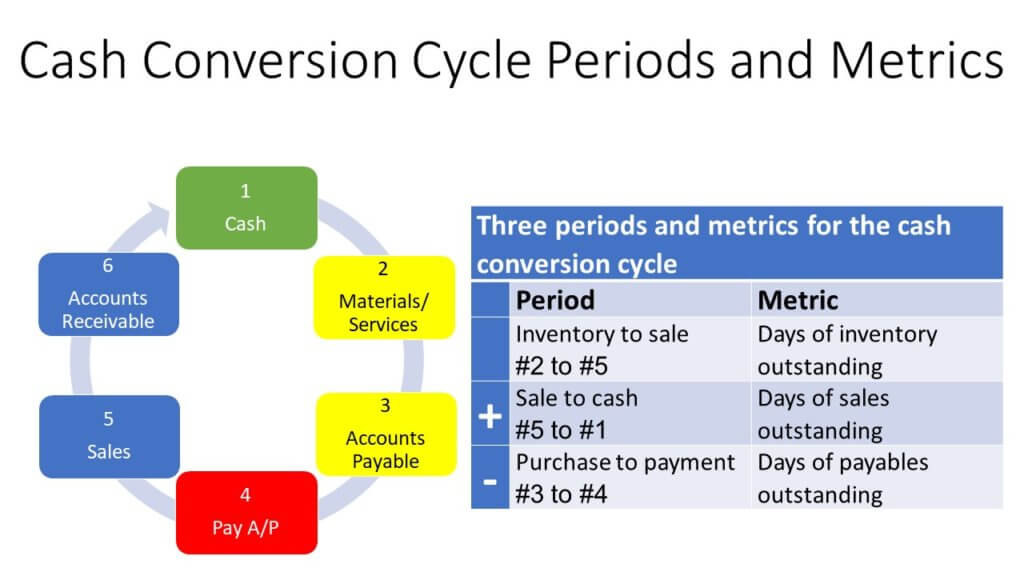

The cash conversion cycle is the length of time from when you pay cash to suppliers or employees until you receive cash on your sales. The art of managing your cash conversion cycle is to delay the outflow of cash as long as possible while accelerating the inflow of cash.

The cash conversion cycle can be broken into three periods:

- Inventory to sale

- Sale to cash

- Purchase to payment

The graphic above shows the three periods and how they map to the cash flow cycle. I’ll explain the metrics for each period later.

Imagine a distributor who buys their inventory on January 1 and pays for it on January 15. They take the product and put it in their warehouse, where it sits until they sell it on April 1. They collect cash from the buyer 60 days later, on May 31.

Let’s break that down into the three periods:

- Period 1 of Inventory to sale from January 1 to April 1 is 91 days

- Period 2 of Sale to cash from April 1 to May 31 is 60 days

- Period 3 of Purchase to payment from January 1 to January 15 is 14 days

The total cash collection cycle in this example is 137 days (i.e., 91 days + 60 days – 14 days). They spent their cash on January 15 and didn’t get it back until May 31. They lost that cash for over a third of the year!

Shorter cash cycles lead to better cash flow. Some ways to shorten the cycle include:

- Send invoices as early as possible

- Provide incentives for quick payment

- Contact past-due customers and ask when they expect to pay

- Factoring

- Not paying vendors until the due date

- Negotiating payment plans with vendors

The cash conversion cycle’s three time periods each have a metric that companies may decide to elevate to a KPI:

Days of Inventory Outstanding (DIO)

- Explanation: The days of inventory outstanding is the average number of days it takes to sell inventory.

- Formula: Average inventory / (cost of goods sold/365)

The last part of the formula (cost of goods sold/365) is your average daily cost of goods. Divide your current or average inventory by that daily cost to calculate the number of days it takes you to sell inventory. Average inventory is calculated as starting inventory plus ending inventory divided by two. This averaging method works if your starting and ending inventory are representative of your average inventory. If not, you want to average daily, weekly, or monthly balance.

- Lower numbers are generally better.

Days Sales Outstanding (DSO)

- Explanation: The days sales outstanding is the number of days it takes to collect cash from sales.

- Formula: Average receivables / (net sales/365)

The last part of the formula (i.e., net sales/365) is your average daily sales amount. Divide your current or average accounts receivable balance by your daily sales to calculate the number of days it takes to collect cash from sales.

- Once again, lower numbers are better.

Days Payables Outstanding (DPO)

- Explanation: The days payable outstanding is the number of days from the purchase of materials or labor until you pay cash for them.

- Formula: (Average payables + average accrued liabilities) / (cost of goods sold/365)

The last part of the formula (i.e., cost of goods sold/365) is the average daily cost of goods.

- Higher is better for this metric, but you don’t want this metric to be so high that you anger your vendors and employees.

Credit losses will also likely rise. You may want to tighten credit lines to some or all of your customers. This is something that can also be done before the recession hits. Monitor which customers are more likely to have weakened cash flow. You may reduce credit amounts to them or require payment on or before delivery.

Companies low on cash will want to increase the frequency of their cash flow forecasts. These forecasts determine who gets paid and when they get paid. It helps them decide if it’s worth offering discounts on invoices to incent customers to pay sooner. The company may decide they need to factor invoices to improve cash flow. A healthier company may use cash flow forecasts to project if they need to request an increase in their line of credit. In the darkest scenario, the forecast shows how long a company has until it must close or declare bankruptcy.

For more information on cash flow management, check out my course titled Managing Cash Flow.

Pricing

During a recession, desperate competitors may slash prices in a desperate attempt to maintain sales (and maybe their business’s survival). Competitor moves are scary. The impact of emotional reactions to those moves can be even scarier. Short-term reactions can devastate long-term profit.

It’s tempting to reduce the price to one customer to save sales. However, other customers will also want that pricing. Price cannibalization is the loss of sales at one price to sales of the same product at a lower price. Many businesses have one price that’s listed for all customers. Cannibalization then occurs across all existing sales. It’s calculated as the difference between the new price and the old price multiplied by all your sales units. If you quote prices to each customer, you can adjust cannibalization to the percentage of customers that will get the lower pricing.

You then do a break-even analysis to decide whether you lose more profits by lowering prices to keep the sale or by losing sales to customers who will leave if they don’t get lower pricing.

The problem with matching competitor pricing is that they may just lower prices again. This is the downward spiral of a price war. It’s a war of attrition that no one wins. The survivors in a price war are the companies with the lowest costs. An alternative strategy is to focus on the value your product provides to create differentiation from matching on price alone. Be very wary of getting drawn into a price war.

Recessions may force companies to lower prices below their cost. Leadership may balk at this, but those product costs are sunk costs. Storage costs are the remaining true marginal costs. The main determinant for profit maximization at this point is revenue maximization.

I mentioned offering a lower-priced version of your product in an earlier lesson. This is the time to roll out that tactic. It allows you to liquidate excess inventory or retain price-sensitive customers without massive price cannibalization of your existing products.

Check out my pricing course for more details on pricing strategies, tactics, and analysis. I also explain in more detail how to calculate profits at varying prices and sales volumes.

Cost Management

The largest expense at many companies is salaries and wages. Some companies use layoffs to reduce expenses during a recession. There are pros and cons to this:

- Pros

- Can greatly reduce expenses to ensure company survival or minimum acceptable performance

- Method for removing ineffective employees

- Cons

- Large loss of company knowledge

- Training new employees once growth resumes takes time and money

- Severance costs may be high

- Can reduce morale

Some alternatives to reduce compensation costs include:

- Reducing hours

- Early retirement incentives

- Freezing pay or small pay cuts

- Cutting bonuses and incentive pay

Many companies cut costs deemed “non-essential” during a recession. Common expenses that are cut include:

- Marketing

- Professional development

- Capital improvements

- Efficiency and innovation projects

These are ways to reduce current expenses but may come with large opportunity costs. I will discuss this more in the next lesson. Public companies or companies whose owners demand large distributions may be under more pressure to do this. Companies with poor liquidity may have to do this to maintain solvency. Other companies should run scenario analyses to determine whether these short-term tactics will damage long-term profitability.

Decentralization

A Harvard Business Review article by Walter Frick titled “How to Survive a Recession and Thrive Afterward” cites a study of decentralized management during the Great Recession. The study determined that “decentralization was associated with relatively better performance for firms or establishments during the crisis.” Interestingly, the benefits of decentralization faded as economic conditions improved.

Decentralization allowed better adaptation to changing conditions. The researchers proposed that decentralization was beneficial during recessions because the value of local information increases. Employees throughout a company are experts in an aspect of that company. As one researcher said, decentralization matches “decisions with expertise.” Decentralization may also promote experimentation, which is important in an uncertain and turbulent economy.

As an aside, I highly recommend reading the article if you want to learn more about managing a company through a recession. It cites many interesting studies on companies and recessions.

Keeping Focus

The ability to make good decisions can be hampered by fears and distractions during a recession. One way to maintain focus is via KPIs. Making efforts to improve these will be a much better investment of time and money than other reactions a company can make to distractions.

A quote I love is, “The decisions are easy when your vision is clear.” The strategic planning done in the good times provides clarity during the recession. Scenario planning creates the playbook to follow when the economy is much worse than the assumptions in your budget.

Your forecast horizon may be shortened in some analyses. This is driven by the greater business environment uncertainty. I’ve already mentioned more frequent cash flow forecasts, which may be for shorter horizons than during calmer economic times. You may also rely more on rolling forecasts instead of budgets. As I just noted, the annual budget may have become irrelevant. Rolling forecasts allow constant updates of the key business drivers and the profit outcomes from forecasts of those drivers. Check out my rolling forecasts course for more details on the benefits of these forecasts and how to efficiently develop them.

Improper extrapolation is a problem before a recession hits and before it ends. Extrapolating good times into the future may make a company unprepared for a recession, and extrapolating bad times may make a company unprepared to grow in an expanding economy. Monitor leading indicators for signs that the recession is abating. This will give you time to prepare for growth.

Opportunities in Recessions

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Gulati, Nohria, and Wohlgezogen wrote an exceptional 2010 article in the Harvard Business Review (HBR) titled “Roaring out of Recession.” In it, they discuss a study they conducted on company performance during the recessions of the early 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s.

First, an ugly finding is that 17% of the companies went bankrupt, were acquired, or became private. The silver lining to that cloud is that 83% of companies – the vast majority – survived the recession.

Well, it turns out that there is still a lot of grey cloud in that silver lining. Of the survivors:

- 80% of them had not yet regained their prerecession growth rates for sales and profits three years after a recession

- 40% of them hadn’t even returned to their absolute prerecession sales and profits levels by the end of that time period

These statistics are sobering. They also reflect something I mentioned in the lesson on the financial challenges of a recession. The average recession is 17 months long, but that’s only from the peak to the trough of the economy. It takes many more months for the economy to recover from past levels. Both individual companies and the economy as a whole are still recovering or just starting to reach new levels at the three-year mark.

The study broke companies into four groups:

- Companies that made primarily defensive moves to avoid losses and minimize downside risk. These companies tended to make large cost cuts, including layoffs.

- Companies that made primarily offensive moves that might provide upside benefits. These companies made larger investments and acquisitions.

- Two groups of companies that combined both defensive and offensive moves.

The companies that made primarily defensive moves fared worst. Those that made primarily offensive moves were the second-lowest-ranking group. Companies with a combination of strategies fared best.

The researchers found the following to be the most effective mix:

- Investing in assets such as plants and machinery

- Cutting costs mainly by improving operational efficiency rather than by slashing the number of employees relative to peers

- Developing new business opportunities by making significantly greater investments than their rivals do in R&D and marketing

Asset Purchases and Financing Costs

Poor companies overleverage when borrowing costs and asset costs are high. When a recession hits, that high debt service is an anchor on profits and cash flow. Smart companies buy and borrow when prices are low. Vendors desperate to make sales in a downturn often sell equipment at much lower prices than they commanded during good economic times. Real estate may be much cheaper. Weaker companies may want to or need to sell to stronger ones. Once again, the deals are in the downturns.

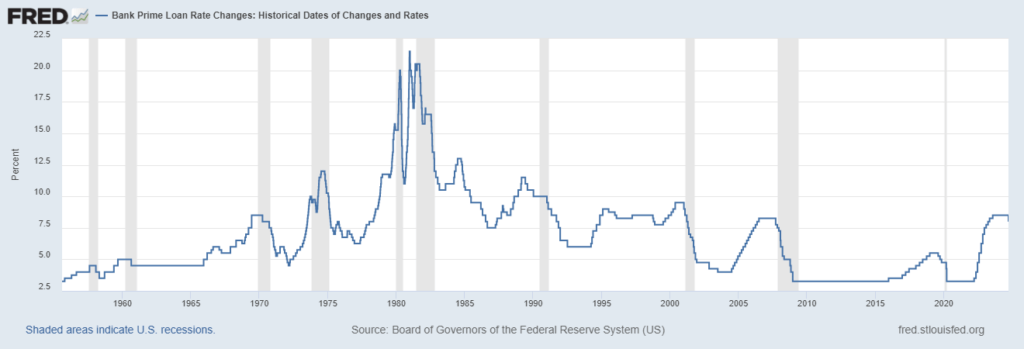

Financing or refinancing those assets is also cheaper during a recession. Below is the Prime Rate since 1955. Business lines of credit and other floating-rate loans are often indexed on the Prime Rate. Recessions are shaded in grey.

The Prime Rate tends to drop from the start to the end of a recession. These drops can be 5% or more.

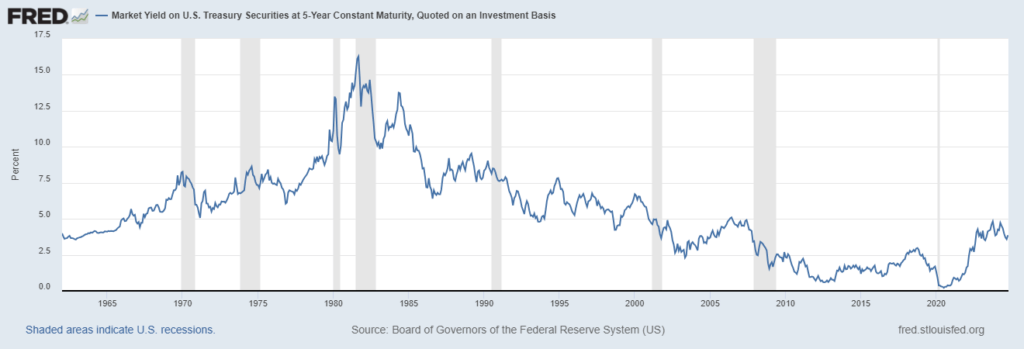

Below is the 5-year Treasury rate since 1962. Equipment loans with maturities of five to seven years and commercial real estate loans with rates that reset every five years have rates that may follow the pattern of the 5-year Treasury rate. Recessions are once again shaded in grey.

Once again, this rate tends to drop during recessions. It doesn’t drop as much as the Prime Rate, but the rate can be locked in for five years. The Prime Rate can change at any time and often starts rising after a recession.

Cutting Costs and Creating Business Opportunities

Investments in assets are often part of a much larger effort to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of processes. The reduction in demand during a recession creates the time for staff to research and implement these improvements. In addition, there is now more time for employee training.

The best use of employees’ time during the economic expansion was likely production. Now, the company can invest to prepare to meet the demand of the next expansion with better efficiency and lower costs.

I mention researching efficiencies and improvements because some are more effective than others. Some companies may make across-the-board spending cuts. This may be a faster way to make cuts and may seem fairer to some people. However, these cuts often come with long-term damage. Morale falls. Good investments are curtailed, while poor investments are reduced but not eliminated. Targeted cuts and investments are more effective.

I noted earlier that these investments may not provide positive profits or cash flow in the first months after implementation. The payback may take many months and may increase as sales increase. Thus, companies with cash and a long-term outlook are much more able and willing to make these investments.

The companies that entered a recession with low cash balances may not have been able to make these investments during the downturn, even if they wanted to. They entered the recession weak and missed opportunities because of their weakness.

New Business Opportunities

The focus during a recession moves from maximizing profits to surviving for companies tight on cash. For those with cash, the focus changes from patience with cash to investing in opportunities.

I’ve mentioned mergers, capital expenditures, and employee training. Marketing and advertising costs are areas that many companies cut during recessions to maintain current profits. According to Nielsen Marketing Mix Models, “Brands that go off-air can expect to lose 2% of their long-term revenue each quarter and, when they resume media efforts, it will take 3-5 years to recover equity losses resulting from that downtime.”

Other companies may invest in marketing and advertising during the recession because they can get better pricing.

Throughout this article, I’ve emphasized that companies should look for targeted opportunities. How does a company do this? They can revisit a common first step in strategic planning – environmental analysis. The recession has likely changed many of the observations and conclusions from the last analysis.

A common useful tool for this is SWOT analysis. Here is how the acronym would apply in a recession.

- Strengths – This allows companies to capitalize on the opportunities I’ve discussed in this lesson. Hopefully, the company built durable strength during the previous economic expansion that can be drawn on during the recession.

- Weaknesses – These may be significant enough that a company must focus on these during the recession for survival. For others, the investments I discussed will reduce the weaknesses. In other words, recessions are an excellent time to reduce weaknesses.

- Opportunities – That’s what this lesson was all about. Interestingly, we have seen that recessions provide very good opportunities for the few companies in a position to capture them.

- Threats – The recession may now loom as the largest threat by far. A company can look at how the recession is impacting earnings and cash flow to diagnose the weaknesses that caused those drops. The recession is out of the company’s control, but their responses to improve the company are in their control.

Two other models that focus on the business environment are PESTEL analysis and Porter’s Five Forces Models. For more details on this, check out my course titled “Business Environmental Analysis: Finance’s Role.”

In summary, when are opportunities for profits the highest? When competition is lowest. This happens after the weak and irrational ones have hibernated or been weeded out in a recession. How can you position your company to be the one that captures opportunities and not the one that is consumed with triaging weaknesses?

For more info, check out these topics pages: