The basics of cost-plus pricing, along with its pros and cons.

Cost-plus pricing involves adding a markup to the cost of producing or acquiring a product to establish the final price.

It’s often used in industries where it is challenging to assess the market demand and set prices based on competitors or market conditions. It provides a straightforward way to ensure that a business covers its costs and earns a targeted profit.

The formula for cost-plus pricing seems straightforward: Selling Price = Cost + Markup

However, let’s dig a little more into the components of “cost” and “markup” to see some of the challenges of this pricing policy.

Cost

Cost refers to the total cost incurred in producing, manufacturing, or acquiring the product. It frequently includes variable costs (e.g., materials, labor, and direct production expenses).

Two other types of costs may be included in costs or may be factored into the margin:

- Fixed costs (e.g., rent, salaries, and depreciation)

- Other expenses, such as overhead and administrative costs

Like so many analyses, choosing which cost to use as a starting point can greatly influence the outcome of the analysis. Some options include:

- Marginal costs: Marginal costs are the change in costs due to a change in production volumes. These are often the only relevant costs of a forward-looking decision. All other costs are sunk and irrelevant.

- Standard costs or past average costs: These costs are often easily calculated from financial reports. They may be the outputs of an analysis from costing methods like activity-based costing. As noted above, these costs may only include variable costs or may reflect full absorption costing, where overhead amounts have been allocated to products.

- Inventory costs or replacement costs: These are two other options. Many companies can easily use inventory reports to find a cost per unit as a starting point for pricing. Other people may say a more relevant cost is the cost to replace inventory. This is reflected in a classic debate on how gasoline should be priced. Should the price of gas be based on what the station paid in the past for the gas in their tanks or what it will cost them to replace the gas they are selling?

- Product costs plus ancillary service costs: The “total” costs of a product may go far beyond the costs of production. There may be customer service costs, product returns, and other costs that need to be added to direct production costs.

Cost-plus pricing also suffers from a “chicken vs. the egg” problem. How can you set costs unless you know the volume you might sell? How can you estimate the volume without starting with an assumed price? In other words, which truly comes first as an assumption in cost-plus pricing: the cost or the price?

Costs per unit vary greatly based on the volumes you will produce. At certain volume thresholds, you will incur a step fixed cost, which will greatly increase costs above the pure variable costs. Step fixed costs are costs that don’t change over a range of production but then greatly change when a threshold is reached.

The per-unit allocation of fixed costs also varies greatly based on assumed volumes. If you have $1,000,000 of fixed costs, the per-unit allocation is $1,000 at 1,000 units of production but only $100 at 10,000 units. That’s a $900 difference in price using a cost-plus pricing methodology!

I’ll return to this “chicken vs. the egg” problem later in this lesson.

Markup

The markup is the amount added to the cost to determine the selling price. Markup can be expressed as a fixed amount or a percentage of the cost. Like costs, there are options for determining the markup:

- The profit margin the business wants to achieve

- A company’s cost of capital

- As noted earlier, if costs are defined only as variable costs then a company might include fixed costs and overhead in the markup in addition to a profit amount.

- There are rules of thumb in some industries for markup amounts. When I worked in restaurants, pricing was often set at three times the costs. I had a client in another industry that billed custom work at two times their cost.

These and other common markup options can reasonably answer the question, “What is the correct overall amount of markups for my company?” The question they don’t often answer well is, “What is the correct markup for each product?”

For example, grocery stores are notorious for having loss-leader products like milk and eggs that attract people to the store in the hopes that those shoppers will then buy other products with high margins. The margins of the loss leaders and the other products will be radically different.

I noted that restaurant prices were set around three times food costs at restaurants. At a restaurant I worked at, soda and our little loaves of bread were priced at ten times their costs. Margins on alcohol were high. Margins on main dishes were low. This is why servers are coached to upsell customers on drinks, appetizers, side dishes, and desserts. Those are the high-margin products.

Advantages of Cost-Plus Pricing

Cost-plus pricing has been historically very popular for the reasons below:

Simplicity and Transparency

Cost-plus pricing is straightforward and easy to understand. Both employees and customers can quickly grasp how prices are determined, which can lead to more transparent and predictable pricing. This can make it appear more objective and defensible to company employees, especially sales staff, who must negotiate pricing with customers. Administering pricing policies with this methodology may also be easier.

Cost-plus pricing also requires much less information and effort gathering information than other methodologies. The costs often come from costing information a company already has. Adding a markup to the costs is a simple calculation compared to other pricing methods.

Cost Recovery

This pricing method ensures that a business covers its production costs, including both variable and fixed expenses. The margin provides a safety net for the company to avoid selling products at a loss.

Profit Control

Businesses can easily control and adjust their profit margins by setting the markup percentage. This allows them to achieve their desired profit levels consistently. Some consider it a “guaranteed profit,” which may not be true. I’ll explain this further in the disadvantages section later.

Stability

Cost-plus pricing provides a stable pricing structure, making it suitable for industries with high production costs or where market conditions are volatile. It helps companies avoid dramatic price fluctuations. This is especially true when competitors also use a cost-plus methodology or have stable pricing. Often, stability is based on the assumption that all competitors have similar cost structures. However, it does not guarantee that all competitor require the same margin on their costs in cost-plus pricing.

Risk Mitigation

Cost-plus pricing can be beneficial when the cost of goods or services fluctuates due to factors like inflation, changes in supply chain costs, or unforeseen disruptions. Companies can adjust their markup to adapt to these changes and maintain profitability.

Perceived Fairness

Customers consider pricing to be fair when companies base their pricing on costs plus a reasonable margin. Employees also see this as fair to both customers and the company.

Government Contracts and Regulation

Cost-plus pricing is often required or preferred in government contracting and regulated industries. This ensures that costs are transparent, auditable, and fair for all parties involved. Some of the grants and contracts I had when I was the CFO of a community health center were based on cost recovery.

Disadvantages of Cost-Plus Pricing

Despite its popularity, most pricing experts take a very dim view of cost-plus pricing. Here are some of the significant drawbacks they see with it.

Ignores Market Demand

The biggest drawback of cost-plus pricing is that it doesn’t take into account what customers are willing to pay based on their perception of the product’s value. It’s completely blind to the market and customers. This can result in underpricing if the perceived value is higher than the cost-plus price or overpricing if it’s lower, potentially leading to missed revenue opportunities.

In a good market, you leave money on the table. Your revenue is capped by your costs and your margin. The purpose of pricing is to maximize marginal contribution, which cost-plus pricing ignores.

In a bad market, you overprice and lose sales volume and revenue. The loss of volume causes your per-unit costs to increase. Your fixed costs are spread over fewer units. If you are beholden to a cost-plus pricing strategy, you would then raise prices to cover the higher unit costs. This puts you further out of the market in a pricing death spiral.

Lack of Competitiveness

Relying solely on cost-plus pricing can make a business less competitive in markets where competitors use different pricing strategies, such as value-based pricing or dynamic pricing. This can lead to a loss of market share.

Inefficiency

It may not incentivize cost control and operational efficiency within the organization since the pricing is primarily cost-driven. Costs are assumed to be able to be passed on to customers. This can lead to higher costs and reduced profitability over time.

Difficulty in Setting the Cost and Markup

Determining the appropriate markup percentage can be challenging. If the markup is too low, it might not provide a sufficient profit margin, while a markup that’s too high can deter price-sensitive customers.

Companies may struggle to determine what a “fair” return margin is for each product or component of a product. This can get political very quickly when different products under different managers are told to set their pricing based on different margins. Fairness is assessed by employees not only by fairness to customers but also by fairness between departments.

Even picking costs, which would seem much easier to determine, can be difficult. I’ve built profitability systems and then spent hours justifying output costs from it. The assumptions in the system came from the people now challenging the results. I noted earlier that companies need to decide whether to use marginal costs, standard costs without overhead allocations, or fully-loaded costs.

Focuses Company Energy on Internal Analysis Instead of a Customer Focus

Company energy is focused on setting internal costs and margins. These discussions can be contentious and suck company energy. That time and effort may be better spent exploring opportunities, opportunity costs, and how the customer values the product.

Based on Irrelevant Past Amounts Rather than Future Costs

Past costs that are irrelevant to forward-looking economic decisions are called sunk costs. The sunk cost fallacy or sunk cost bias is incorrectly using these costs when making decisions. Cost-plus pricing is extremely prone to this.’

The clearest example is when past fixed costs are included in the cost or margin used for cost-plus pricing. Company staff who point to cost-plus pricing to claim, “We have to make a profit” or “we can’t sell below cost” may cause the company to pick a price that does not maximize the revenue and profit the company can make going forward. Anyone who has had to liquidate excess inventory at a steep discount knows that you have to accept whatever price you can get.

I noted earlier that the costs in cost-plus pricing are often set by historical accounting rather than replacement costs or incremental costs. Matching past costs to future sales follows GAAP (generally accepted accounting principles) but isn’t effective for financial decision-making. Accounting and finance staff can be especially prone to GAAP-induced blindness. This furthers the image of them being “out of touch” with customers, markets, and maybe even reality.

Risk of Underestimating Costs

Businesses that use cost-plus pricing may underestimate their costs, especially if they fail to account for all relevant expenses, including indirect and overhead costs. Reliance on cost data assumes that cost calculations are accurate and up-to-date. Inaccurate cost data can lead to incorrect pricing decisions. This can lead to lower profits or losses.

Lack of Flexibility

Cost-plus pricing can be inflexible when market conditions change. It may not allow a company to quickly adjust prices in response to changes in demand, supply, or competitive pressures.

Complexity in Multi-Product Businesses

In businesses that offer a wide range of products or services with varying costs and demand, managing and applying a consistent cost-plus pricing strategy can be complex. If all products are assigned the same margin, you can’t easily differentiate products for pricing strategies. For example, you can’t pair loss leaders and high-margin products to create profitable bundles of customer purchases. Also, different customers have different costs to serve them, so you must segment your customers, products, or channels and determine the cost and margin for each.

Insights from Cost-Plus Pricing

You may think that cost-plus pricing concepts are irredeemable after that litany of dysfunction. All is not lost.

First, there may be times when cost-plus pricing may be useful. It might work for products with a high percentage of variable costs in companies with low overhead. Some small businesses fit that description.

Cost-plus pricing may be a good starting point for new products that have no competitors and little customer awareness of the product. It may be very difficult to assess a customer’s willingness to pay. You may start with cost-plus pricing and then adjust from that price over time.

You may look inward at costs and capacity constraints to change pricing. For example, you may charge higher prices during periods of higher capacity utilization and lower prices during lower utilization. This is common in many industries. Others can utilize this method to avoid steps costs while still capturing some business during times of excess capacity.

Once again, I caution in some of the examples I just listed that the relevant costs for setting cost-plus pricing are marginal costs, not fully-loaded historical costs.

CVP and the Chicken vs. the Egg

How do we tackle the chicken vs. the egg issue I brought up earlier? Cost-plus pricing implicitly assumes a volume to determine costs. It also assumes that the market will buy that volume at whatever price is calculated. That is sheer fantasy.

Where can we start? I have a dear friend named cost-volume-profit (CVP) analysis. The formula for CVP is:

Gross Revenue – Total Variable Costs – Fixed Costs = Profit

This can be further broken down into:

(# Units Sold X Price) – (# Units Sold X Cost) – Fixed Costs = Profit

Cost-plus pricing and CVP share many of the same components. Every formula needs some assumptions to be set to calculate a result. Cost-plus pricing assumes a volume (e.g., # of units), variable cost, fixed cost, and profit to determine a price. Cost-plus pricing treats fixed costs as variable costs to determine price as an output. Sales volume is treated as a fixed assumption and price as an outcome.

Let’s step back and determine which of the assumptions are most certain and most in your control. My guess is that they are your costs. Let’s say your owners demand a certain profit margin, as most owners do. That leaves price and volume as the most uncertain variables. These are the ones we need to model.

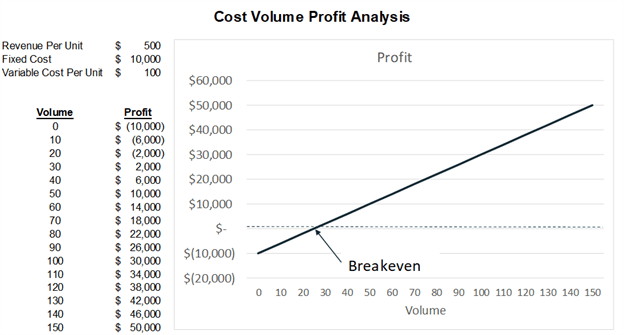

My friend CVP is usually shown as a straight-line guy, like this:

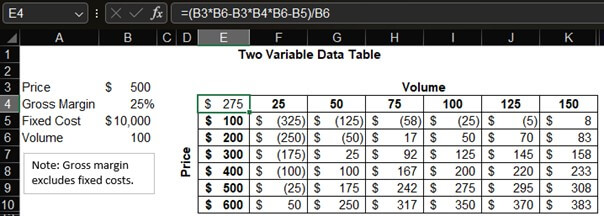

However, CVP has a sibling named two-variable data table that allows us to model two assumptions at once. That complex animal looks like the image below. This data table finds the maximum variable cost to achieve a given minimum margin (and cover a given fixed cost) for various prices and volumes.

The first column is a set of prices, the top row is a set of volumes, and the numbers in the rest of the table are per-unit costs. Other assumptions are listed to the left of the table. Each intersection of a price and volume in the table is the maximum per-unit cost to achieve the margin target on the left of the table (cell B4).

The question for company leaders is: Can we produce the product at the variable cost or less at all likely intersections of prices and volumes? For example, can we produce each unit for less than $275 if we expect to sell 100 units at $500? If so, we’ll achieve the margin we want and cover fixed costs. If we only sold 400 units at $500, our variable costs would need to be $200 or less to achieve our desired margin and profit.

The table cells with negative numbers mean that costs would have to be negative to achieve the margin; this is impossible in reality, of course.

All this means that we can start by setting up a data table that models the two uncertain assumptions of price and volume. If we assume a profit assumption and the fixed costs (or ignore them as sunk), we can back into what variable costs need to be.

So, it’s best to start with an array of volumes and prices to determine if we can produce the product at a cost low enough to achieve our target profit at varying volumes. It flips standard cost-plus pricing backward, but it reflects what’s really most uncertain in pricing.

For more info, check out these topics pages: