I had lunch with a friend who is the head of lending for a $4 billion financial institution. I asked him what he wished companies knew. His answer was, “Companies get into trouble in the good times.”

He wasn’t saying that companies fail during good economic times. Rather, they make decisions that cause them financial stress when a recession hits.

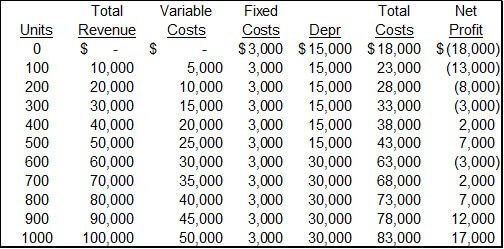

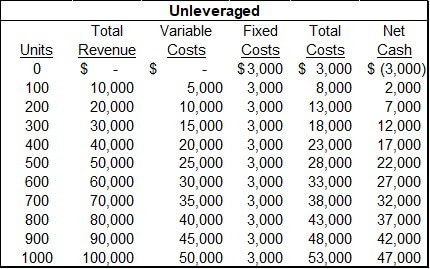

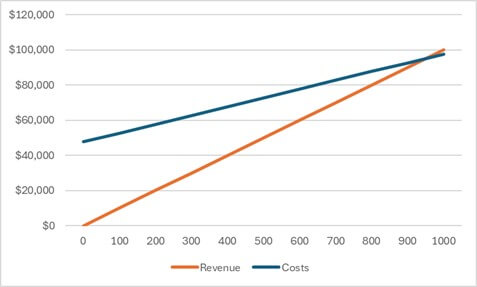

Let’s look at some numbers to see how these concepts play out in a recession. Let’s assume a company sells a product for $100 per unit and has variable costs per unit of $50. They buy a $150,000 piece of equipment that’s depreciated over 10 years. This equipment has a maximum capacity of 500 units, so they need a second one when their production exceeds 500 units. I also assume $3,000 of other fixed expenses. Below are the company’s annual revenue and costs at various units.

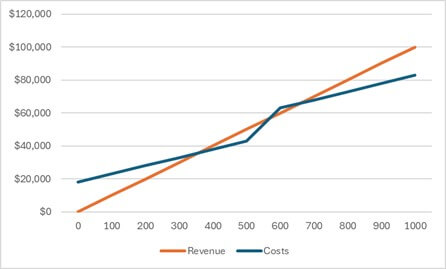

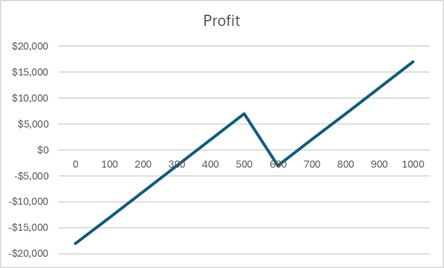

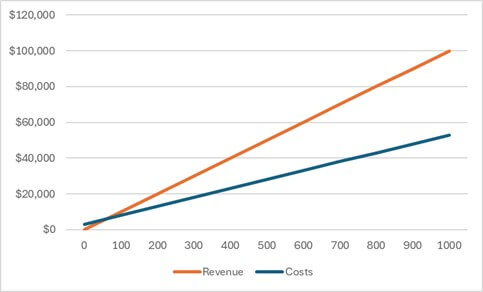

The company loses money until they produce somewhere around 400 units. At 501 units, they have to buy another machine. This lowers their profit below break-even from 500 to 600 units, but they are again profitable at volumes above this. Here is a graphical summary of this cost-volume-profit (CVP) analysis:

In good times, companies lay the groundwork for their demise in a recession. They ratchet their costs up with growth. When sales falter, they cannot maintain profits as they try to scale down.

Like most companies, this company was losing money in its early stages when production volume was low. They finally broke even at around 400 units but were happy to buy another machine to achieve even higher sales and profits to meet forecasted demand. Let’s say this company was producing 800 units at the peak of the economy before the recession hit. They were making a $7,000 profit, and everyone was happy.

Then, the recession hit. Sales started dropping. Intuition may say that their profit will follow the graph’s profit line from right to left as volumes drop. Unfortunately, that’s not what happens. They have two machines. Selling one, especially during the downturn, will return pennies on the dollar that they paid. As volumes fall below 500, they have to decide what to do about the second machine. They could sell it and realize an immediate loss on the sale. They would go from a net profit of $7,000 before the recession to a six-digit net loss in the recession.

The other option is to hold onto the machine, hoping it can be used again when good times return. This leads to another mistake many companies make. When a recession starts, we don’t know how severe or long it will be. Entrepreneurs and business leaders tend to be overly optimistic, so they may not see the need to make significant cost cuts until there is no other option. Further, cutting costs often means making hard decisions about staffing and reducing revenue potential. To avoid these decisions, leaders may be stuck in a cycle of analysis paralysis trying to find certainty, or at least comfort, in an uncertain world. Finance staff are tied up doing this analysis rather than more profitable work.

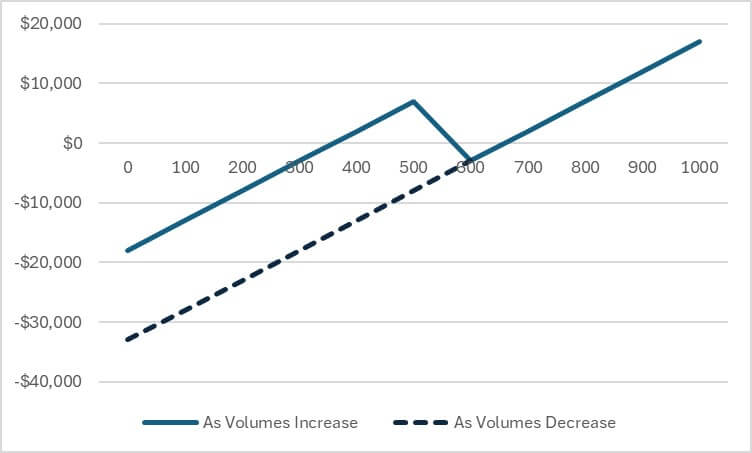

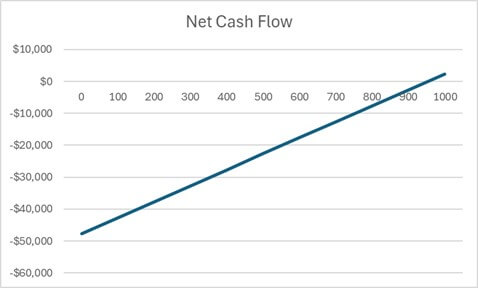

Both machines continue to depreciate if the company doesn’t take an immediate loss on the sale or abandonment of the second machine. The profit line the company follows as volumes decrease follows the dotted line in the graph below.

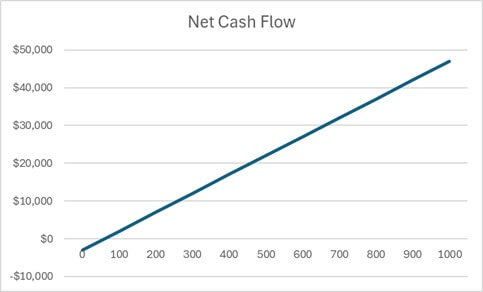

The break-even point for companies increases as they incur fixed costs. As sales drop, you can’t scale down costs on the same path on which they scaled up. The analysis to this point has been on profits. As I said earlier, companies fail because of a lack of cash, not because of a lack of profits. The analysis below will look at this company’s net cash flow.

An assumption for the graphs below is that the company has already purchased the two machines. In the first scenario, the company used an equity infusion to fund the machine purchase. The table below summarizes their cash flow at varying volumes:

The machines are a sunk cost, so they aren’t listed in this analysis. Net cash flows are positive at low sales volume amounts. Below are graphs of the unleveraged company’s cash flows. They have positive cash flow at volumes over 100 units.

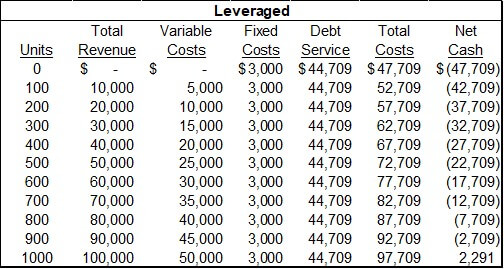

Now, let’s assume that a similar company financed the machines with debt (i.e., leverage). Why companies choose debt can be explained by both traditional finance and behavioral finance. Leverage magnifies earnings. If two companies have the same return on assets (or sales) and the same total of debt and equity, a company funded with debt and equity will have a higher return on equity than a company funded only with equity. Debt comes with tax benefits. Behavioral finance studies show that overly optimistic business leaders think equity prices for their company are too low, so they use too much debt. Overly optimistic leaders also tend to invest too much in assets, like the machines in this scenario. The risk of losses and bankruptcy is underestimated. Check out my business loans course and behavioral finance course for more on these dynamics.

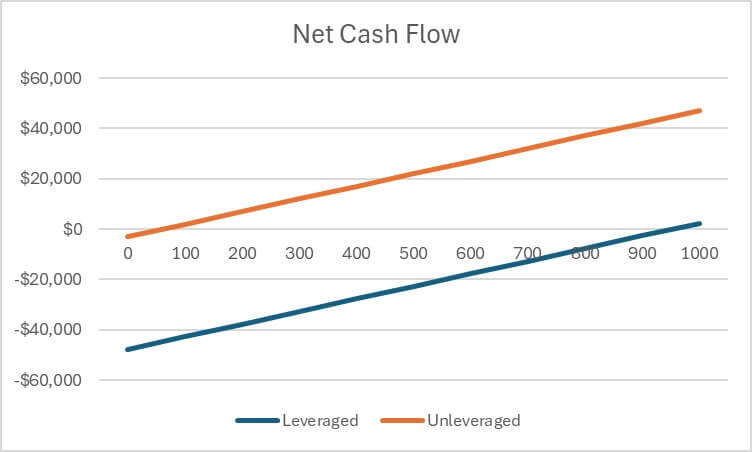

The unleveraged company isn’t burdened with debt payments during the recession. The leveraged company must service the debt payments during the recession. Here’s what cash flow looks like for the leveraged company in this scenario.

This company’s net cash flow is negative for all but the highest volumes. Below are graphs of its cash flow.

Now, let’s look at the graph of the net cash flows of these two companies:

The unleveraged company obviously has a massive advantage in surviving the recession. They have positive cash flows across almost all sales levels, while the leveraged company loses cash at almost all volumes. Yes, the owners had to infuse cash before the recession in the unleveraged scenario, but they have given their company a much better chance of survival if they can be patient in getting cash back from the company. The leveraged company may have to attempt an equity infusion during the recession to stay alive. However, that company may not be able to tap debt or equity funds at this stage.

The unleveraged company may become opportunistic. They can lower prices to gain market share and pressure the leveraged company. The leveraged company may sell to the unleveraged company or may fold. Either way, the unleveraged company then has more pricing power in the market and/or higher sales.

A business can do things to improve its odds of surviving or thriving during a recession. I cover these things in my Financial Management in a Recession course.

For more info, check out these topics pages: