Value-based pricing sets prices based on how much customers value a product. Many pricing experts believe this is superior to basing prices on a company’s internal costs. Let’s explore how value-based pricing can improve a company’s profitability.

Value and Price

Let’s start with some foundational concepts. Your business provides products that have value to your customers.

- Business customers: They use your products in the products they sell to their customers. The product sold to their customers is a combination of the value of your product and the additional value they provide. A manufacturing business customer uses your product as a component part of their physical product. Your retailer business customers sell your product along with other products and services to end customers. The business customer may be the end customer, in which case your product may reduce your business customer’s costs or provide services for their employees.

- Consumer customers: You may provide a financial benefit, like cost savings, for your customers. Often, consumers value products for the subjective benefits they provide (e.g., piece of mind, status, etc.).

Pricing is a sharing of value or splitting of value between buyers and sellers. It’s an exchange of price and value, but both buyer and seller benefit. If both didn’t, then no sale would take place, assuming there is no coercion.

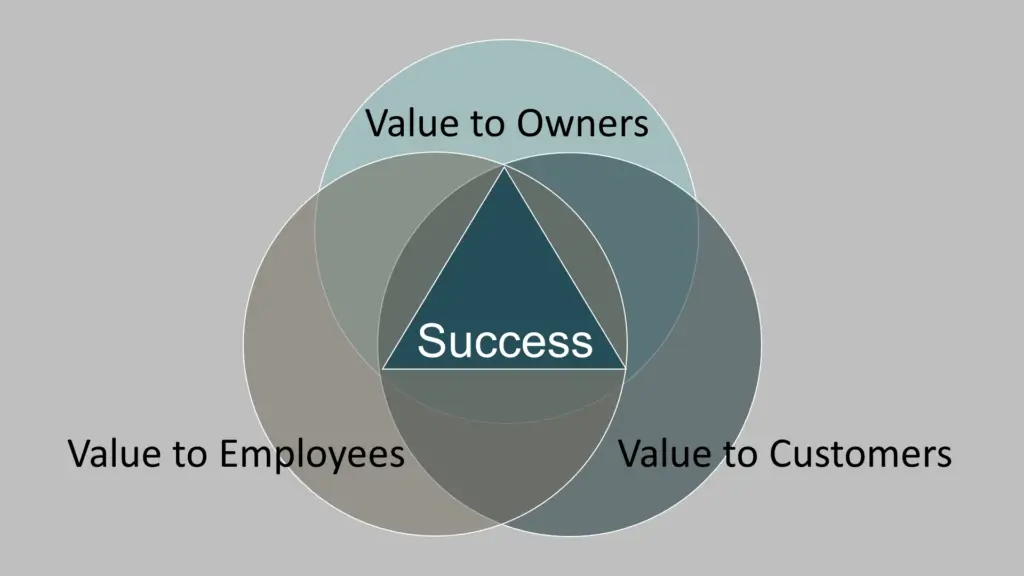

A graphic I like to use to summarize this is my value creation Venn diagram.

Business owners (via their company) receive value when they provide value to employees and customers. True business success is an exchange and sharing of value.

Value-based pricing determines a price by how much the customer is willing to pay for the product or service, given its perceived worth or benefits. Those who set prices take into account the customer’s perspective and the unique value proposition of the offering.

Let’s look at this more linearly. A successful business model is one in which your costs are lower than how your customers value your product. It looks like this:

Financial analysts and management accountants are experts in determining the cost of a product. The trickier questions are:

- How much do customers value (in monetary value) the product?

- Where should pricing be set between cost and value?

The image of cost, price, and value also shows why value-based pricing is considered superior to cost-based pricing. Pure cost-based pricing sets the price at a fixed margin from the cost. Value is not considered when setting the price. Thus, the price could be above the customer’s value for the product, which means no sales. Even if the price does happen to lie between cost and value, it may be set at the wrong point between cost and value. Prices and profits could be higher.

Even proponents of value-based pricing admit that determining value can be difficult, especially for consumer goods where value is very subjective. I’ll explain later ways to estimate value and why Finance staff who are experts in calculating costs can also help assess value.

Use Value

Value to a customer can be broken into use value and economic value. Use value is the practical value or usefulness of a product in fulfilling the customer’s specific needs, desires, or goals.

Some examples include:

- Cost savings

- Improved satisfaction

- More revenue/income

- Less hassle

- Higher status or prestige

- Time savings

- Reduced risk

- Increased performance

- Increased quality

Some of these are easier to quantify than others. Some are very objective. How do we translate these to a number for pricing? Economic value calculations can help.

Economic Value to the Customer

Economic value to the customer (EVC) is the perceived value or utility that a customer derives from using a product or service, considering both the benefits and the price they pay.

It can be summarized in the simple formula: EVC = Benefits – Costs

Let’s look a little more closely at the two components of the formula:

- Benefits are what the customer gains by using the product. I listed examples of use value in the previous section. The benefit can come from obtaining a gain or avoiding a loss.

- Cost is the price paid by the customer and all ancillary costs. Ancillary costs can include implementation costs, training costs, and conversion costs.

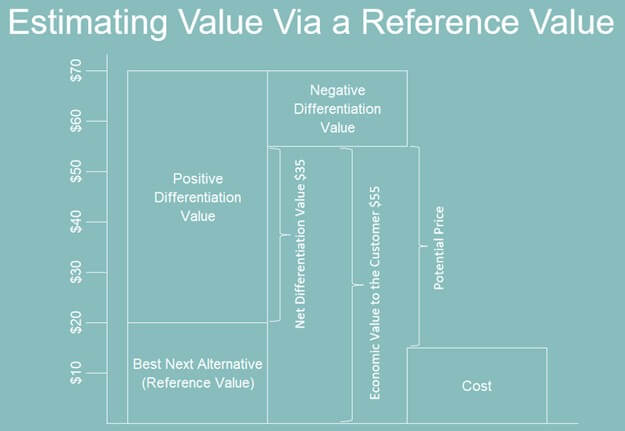

Everything I’ve said so far is true for a customer who wants to optimize their EVC. Absent any competing products to yours, it may be how they calculate the value of your product. However, there are almost always products competing with your product. In this case, customers determine the economic value of your product relative to a reference product (i.e., the product competing with your product). EVC is then determined as: EVC = Reference price + Differentiation value of your product. The following image summarizes all the components of value and pricing.

In this example, your competitor’s product is priced at $20. This is what’s labeled the “Next Best Alternative” or “Reference Value” in the lower left corner.

You have estimated that your product has benefits that your competitor’s product doesn’t, which totals $50. This is the positive differentiation value. On the other hand, you lack $15 of value that your competitor provides. This is the negative differentiation value. The difference between your $50 positive differentiation value and $15 negative differentiation value equals $35 of net differentiation value compared to your competitor’s product.

The total economic value to the customer of your product is the $20 of reference value plus $35 of net differentiation value, which totals $55.

What prices should you consider? The image above said that your price should be between your cost of $15 and the value to the customer of $55. There may be times when you price below your cost for a customer or product. However, the sum of all your revenues from all customers and products must be above your total costs for you to make a profit.

Estimating the Amount of the Components of Net Differentiation Value

You may be so impressed with the value-based pricing image above that you’ve already ordered T-shirts with the image on them for everyone to wear to your next meeting on pricing. It summarizes value-based pricing well. Like all great ideas, the devils are in the details.

Let’s start with the easy parts. You likely know your costs. You may know your competitor’s price. The tricky part is estimating the dollar amount of the components of the net differential value.

First, what provides positive differentiation value? They are benefits that your product offers but your competitor’s product doesn’t provide. I listed types of benefits when I talked about use value earlier.

Negative differentiation value occurs when:

- Your product lacks the value offered by your competitor’s product

- Your product comes with additional costs or drawbacks

Let’s use an example from my banking days. Let’s imagine that one of the bank’s customers is buying a commercial building. The customer claims they got a loan rate of 7% on their building (and yes, everyone talks and shares prices) from another bank. The bank customer has a good working relationship with their commercial loan officer. They know they can get a loan very quickly with their bank, which may be very important to their building deal. Their relationship with the loan officer and trust in the bank’s speed of execution are two components of positive differentiation value. The customer may be willing to pay more than 7% due to these items.

There is one problem. The loan officer is requiring the customer to personally guarantee the commercial loan. The customer will have to dip into their personal finances to make the payments if the rent payments from the building tenants don’t cover the loan payments. The customer claimed they didn’t have to personally guarantee the loan at another bank. This is negative differentiation value.

A business loan could be narrowly defined as dollars. The dollars at the banks I worked at were the same dollars as other banks. The dollar bill from our bank was worth the same $1 as the dollar bills of other banks. We couldn’t create innovative money like a $3 bill. Our cash probably matched that of a study that found that 92% of U.S. paper currency contains traces of cocaine.[1]

This loan example shows that even products that appear to be commodities are often combined with services and subjective aspects that constitute the full solution as experienced by the customer.

How do you value the components of net differentiation value when they can be so subjective? What is the value of the officer’s relationship with the customer? How much does the customer value a speedy loan process? If all things were equal, at what rate difference would the customer go to another bank to not have to personally guarantee the loan?

The answer is a net 1.50% for all these items. Just kidding – I have no idea, and neither does anyone else.

The value of the speed of the loan could be calculated as the probability of the deal falling through without a quick loan times the profitability of the deal. These are tough numbers to estimate, but there is a logical basis for the calculation.

The value of the relationship is much more subjective. Over time, loan officers can estimate a range of the value of the relationship. They knew times when all things were equal between their loan and a competitor’s loan, but their price was slightly higher, and the customer still chose them. There were other times when their price was high enough that the customer went to the competitor. A similar estimation could be made about the sensitivity of customers to a personal guarantee.

Many components in business-to-business products can be calculated fairly objectively. The value to the business customer is a cost savings or an increased price they can charge to their customers. Value when selling to consumers is much more subjective. Consumer products may allow the customer to save money, which a company could objectively calculate a value for. Value is never purely subjective or purely objective. The example I used showed examples of subjective value in a business-to-business transaction.

Behavioral finance also provides insight into valuing differentiators. Value to the customer can come from obtaining a gain or avoiding a loss. Prospect theory shows that a loss is perceived to be twice as large as a gain of the same dollar magnitude. In other words, the pain from losing $100 is equal to the happiness from gaining $200. They are both perceived as $200 events. This means the value adjustment for avoiding losses as positive differentiation may be greater than the dollar amount you estimate. Conversely, losses of benefits as negative differentiation may be perceived by the customer as larger than the initial objective dollar estimate you may make.

Pricing strategies and policies often require a cross-functional team to make value differential estimates. Production staff and product experts know all the technical ways a company’s product differs from the competition. Sales and marketing people know their customers well. They have good insights into the subjective value customers place on a product. They can also identify the components of net differentiation value. If the positive differentiation is a cost savings by the customer, finance staff are experts at calculating that. Finance staff calculate costs internally for the company they are at and can use the same skills to estimate the savings of customers. They can also help calculate the value of benefits to business customers of other types of differential value.

The Opposite Logics of Cost-Plus Pricing and Value-Based Pricing

Cost-plus pricing and value pricing aren’t just calculated differently. They come from very different perspectives on pricing, profitability, and product strategy.

A cost-plus pricing model starts with product costs, adds a margin, and then asks whether that price would work in the market. Price is the outcome of the equation. In reality, most companies must accept the price that markets provide. If the calculated price is too high, then accountants have to keep calculating potential costs to find a price that works, or they have to rearrange the formula to solve for cost given a price.

Value-based pricing starts with the value a product provides and the price it could fetch. It then asks whether the product could be produced at a low enough price for an acceptable margin. Cost is then seen as the number to solve for. Production costs are often more controllable than price.

Value is measured by how well a customer’s problem is solved by the product’s solution. Value-based pricing starts with product-market fit. This is truly how value creation and successful products are developed.

Value Proposition Budgeting

Understanding what customers value and whether they are willing to pay for that value should drive your company’s strategies and costs.

Value proposition budgeting, also known as priority-based budgeting, prioritizes expense allocation based on which products or services produce the highest value. Instead of applying incremental adjustments to expense accounts, value proposition budgeting breaks your budget down by value. The revenue stream that provides the most value will have more resources allocated compared to a segment with a low perceived value.

The first three steps of value proposition budgeting are:

- Identify your customers

- Develop your value proposition

- Develop a budget

The first two steps are strategic and developed by top leaders. Much of this comes from insights from sales and marketing. Step two is tightly aligned with the steps of developing value-based pricing.

Step three is a more tactical step that is often led by finance. Step two and step three determine if you have a profitable business model.

You may not be happy with the profitability that’s first calculated when going through steps one through three. That begins an iterative loop of adjusting target customer segments, the value offered to each, and the cost required to serve each segment. Finance staff can model various prices, volumes, and costs using cost-volume-profit (CVP) analysis, breakeven analysis, and two-variable data tables. I explain these analyses in my Pricing Profitability Analysis and Process course.

This is just a brief overview of value proposition budgeting. Check out my Better Budgeting course to learn more about value proposition budgeting and other budgeting methods.

For more info, check out these topics pages:

[1] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0379073801004017?via%3Dihub