Companies often charge different prices for the same product to differentiate groups of customers or to different individual customers. What are the benefits of this? Should you do this? We’ll explore those questions in this lesson.

Basics of Price Differentiation

Price differentiation or price segmentation means charging different prices. Conceptually, it means charging higher prices for higher value and lower prices for lower value.

Companies often show a customer a high-value product that comes with a high price. The customer then attempts to get that value at a reduced price. The company can counter by reducing the price but also reducing the value. The customer then decides whether the new ratio of value to price is acceptable.

From a profitability perspective, offering higher value to customers often entails higher costs. The higher price of high-value products ensures an acceptable margin. If the customer demands a lower price, offering a product with lower value and cost maintains profitability.

Finance staff are the experts in costs. Sales and marketing staff are the experts in what customers value and customer price sensitivity. These groups can work together to build products or offerings with different prices and value. Finance can help make sure that the offerings have acceptable trade-offs between price and cost to maintain acceptable margins.

Price Differentiation and Price Segmentation

Price differentiation is a pricing strategy in which a company sets different prices for similar products to different customers. Sometimes, it’s defined as setting different prices for the exact same product. Price segmentation can be defined as setting different prices for a product for different groups of customers. It can also include setting different prices for different features of a product.

Charging each customer a unique price based on their willingness to pay (also known as first-degree price differentiation or personalized pricing) would fit the stricter definition of price differentiation but wouldn’t be price segmentation because customers aren’t grouped into categories. Offering different versions or packages of a product or service with varying features and price points can meet the definition of price segmentation but wouldn’t meet the strict definition of price differentiation because the products are slightly different. The terms “price differentiation” and “price segmentation” overlap, and the boundaries are not clearly defined. I will use the term “price differentiation” to include charging different prices for products with slightly different features.

Here are some examples of categories of price differentiation and segmentation:

Different Prices for Similar Customers

Some companies charge a different price to each customer. This is often seen in large business-to-business transactions, especially when the customer sends out a request for quotes from vendors.

It also occurs in large retail sales. Some car salespeople try to identify each customer’s willingness to pay when negotiating the price for a car. The list price or Manufacturer’s Suggested Retail Sales Price (“MSRP”) is used as a high starting point for negotiations.

Charging different prices to different customers is fraught with ethical concerns, especially when there is a large power differential between the vendor and the customer. The vendor may have much more information about the product than the customer. The customer may have limited options, which could be unethically exploited by the vendor. I’ll explore this more later in this lesson and in a lesson on pricing and ethics.

Different Prices for Different Groups of Customers

Customers can be grouped into many different categories. Groups of customers may live in different geographic areas, have different abilities to pay, or be part of groups that society sees as worthy of special pricing (e.g., veterans).

Market pricing is an example of pricing by geography. Some companies set different pricing in different markets.

Student and senior pricing for entertainment are examples of different pricing for different groups’ willingness or ability to pay.

Grocery stores may charge higher prices in urban stores than other stores. This could be because they serve higher-income customers with a higher ability to pay or because of market segment pricing based on higher competitor prices in the urban market.

Different Prices for the Same Products

The same product can be sold at different prices to all customers. One example is bundling. Multiple products are sold for one price that’s lower than the sum of the prices of the individual products.

Another example is when a product has different prices for different times of usage. Hotels and airlines charge different prices for the same room or seat. This pricing is often driven by the varying demand for a fixed supply of rooms and seats. Hotel rooms in vacation spots are much more expensive when the weather is good there.

Electricity may be moving toward widespread time metering. The capacity of electricity production is fairly fixed. Most metering is now done monthly on a monthly rate and usage basis. This may switch to rates that vary throughout the day based on electrical system demand. In this scenario, electricity prices may be lower at night than during peak electricity usage times during the day.

Different Prices for Variations of a Product

Companies can set different prices for different versions of a product. A classic example is to have a Good, Better, and Best configuration of a product or set of similar products. The Good product has basic features for a low price, while the Best configuration has many more features at a premium price.

The price may vary with the channels or feature usage. Banks reduce or waive service fees for customers who use paperless statements. Sometimes, customers get lower prices by ordering online instead of going into a store. Conversely, a store may charge less for in-store purchases if those transactions reduce shipping costs or if the store can cross-sell more products to in-store customers.

Why Price Differentiate?

Every customer values products differently and has a different willingness to pay for a product. Setting just a high price means some customers won’t buy the product because they don’t value it that highly or can’t afford the high price. A low price means more customers will buy the product. Some will pay well below how they value the product. They would have been willing to pay more.

Charging different prices for a product to different customers allows a company to set prices equal to the value each customer perceives for the product and their willingness or ability to pay. Different prices for versions of a product allow better matching of the price to the value each customer wants to receive from the product. All of these improve a company’s profits and can better serve customers.

Price Differentiation Scenarios

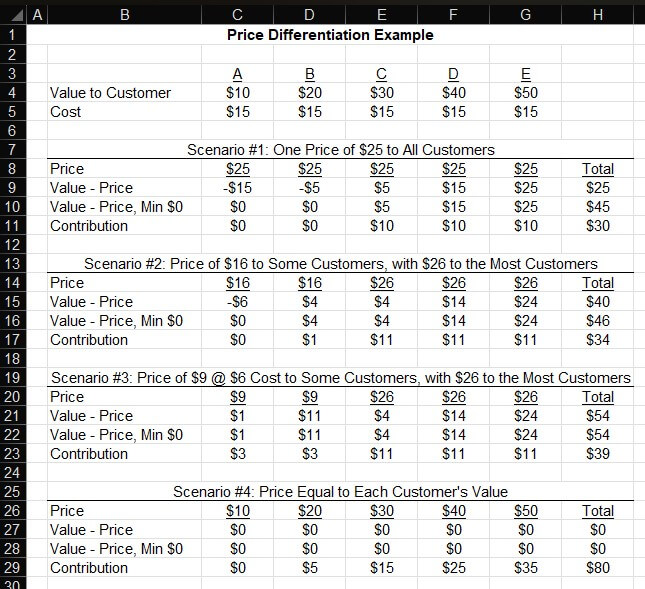

Let’s look at a series of scenarios. The company in this example has five customers, labeled A to E, who each value the company’s product differently. It costs the company $15 to make the product being analyzed.

In scenario #1, all customers are offered a $25 price. Customers A and B won’t buy the product because the price exceeds the value they place on it. Customers C, D, and E buy the product. The company makes a $10 contribution from each.

The company employs a two-price strategy in scenario #2. Some customers are offered a $16 price, and others are offered a $26 price. Customer B now buys the product. The company makes a $1 marginal contribution on customer B and $11 for each of customers C, D, and E. The total net value, as defined as the value minus the price for all customers that bought the product, has gone up from $45 (Cell H10) in Scenario #1 to $46 (Cell H16) in Scenario #2. Total marginal contribution to the company went up even more between the two scenarios. It went from $30 (Cell H11) to $34 (Cell H17). This is an example of charging different prices to different customers.

In Scenario #3, the company wanted to offer a very basic version of their product to customers who place a low value on the product or who have a low willingness to pay for it. They stripped out many of the features and reduced delivery costs, so the total marginal cost of the product is only $6. They lowered the price to $9 for this version of the product. Now, customers A and B both buy the stripped-down product. They place a value on the product that’s higher than the price, and the company makes a positive contribution. Customer B actually has a much larger net value than in Scenario #2. Value to the market and contribution have both increased. The company can now serve more customers. This is an example of having different prices for different versions of a product.

Too Much of a Good Thing

Let’s now look at Scenario #4. The company charges each customer the value they place on the product. The company’s contribution skyrocketed to $80, but all the customers were left with zero net value. This is not a good long-term solution. First, any competitor company whose costs are lower than the value of each customer can offer these customers a lower price. Even if the competitor’s costs are the same as the sample company’s costs, the competitor can profitably poach customers by not pricing away all the value from the customer. Finally, no company can realistically know the exact value every customer places on a product, so scenario #4 doesn’t exist in the wild.

Another mistake is to take choices too far. Let’s say a company has thousands of customers for whom it offers an array of 20 different versions at 20 different prices. Is this like scenario #3, where everyone wins? It’s more likely customers won’t choose if they don’t have to. They may buy from a competitor with a simpler product set and clearer value proposition.

In a study, customers at a grocery store were offered 24 types of jam at a display table on some days. On other days, the display table had only six types of jam. People were ten times more likely to buy one of the jams when there were only six choices versus 24 choices. Too many choices overwhelm our decision-making process. When we’re overwhelmed, we don’t act to make a purchase.

Is It Ethical to Sell the Same Product to Two Different Customers at Two Different Prices?

Some would say no. Don’t do it If that’s what you, your employees, or your customers strongly believe. This may be because “the customer” is thought of as a group of people rather than individuals. In this concept of the customer, everyone in the same group of customers should get the same price, but different groups of customers may receive different pricing.

Some would say yes. The product may be the same, but each customer values it differently. That’s what we saw in the “Why Price Differentiate?” section. Companies offer products at different prices, and customers decide if their value for the product is higher than the price. Absent coercion, many people do not consider this unethical.

There is a situation that’s much more concerning. There are certain products and situations where the fair price of the product is well above the value, often due to limited supply. My value for gas may greatly increase when I’m trying to drive my family out of harm’s way of an approaching hurricane. Does that mean gas stations should greatly raise their rates for me and my neighbors? I will cover this topic in a section on pricing and ethics.

At the end of the day, both value and fairness are determined by the customer. Those are the pricing and ethical boundaries of your company.

Deconstructing Your Products

The key to value-based pricing and differentiation is deconstructing your products. If two products are exactly the same, then value-based pricing says there is no way to justify value differentiation. In that case, the only differentiator is price. The lowest price wins. The lowest-cost producer is the only one who can win the price war, and even they may incur losses.

Before saying your company and the products it provides are the same as everyone else, see if you can identify differentiated value.

Let’s say a company says, “We sell T-shirts.” Is that all they sell? What else do they provide?

- Can customers order shirts via different channels (online, in-store, etc.?)

- Do some customers want faster delivery than others?

- Do some customers want higher quality materials than others?

- Do some customers want more customization of shirts than others?

- Do some customers want a wider range of sizes than others?

I could go on and on. We’re only talking about T-shirts. I bet your company’s products and services are more complex than that. Multiply that by the types of customers you have, and there’s a huge list of value components you provide that are valued differently by each customer.

Identifying all the value components and how customers value them is crucial to:

- Calculating value based-pricing

- Price and product differentiation

Fences

Fences are ways to limit who receives each product or pricing. Without fences, customers willing to pay a high price for your product may pay the lower prices you offer to customers who perceive lower value in your product. It prevents price cannibalization, which is the loss of sales at one price to sales of the same product at a lower price.

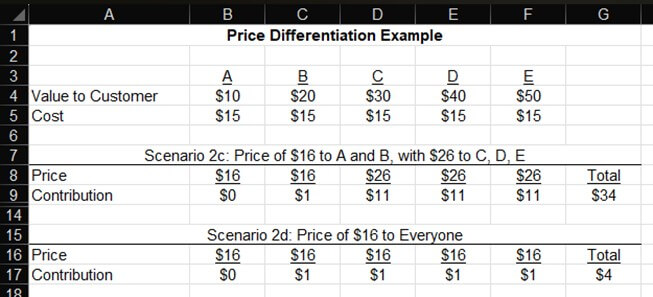

Let’s return to Scenario #2 from my earlier examples. In that example, Customers A and B paid $16, while Customers C, D, and E paid $26. The image below shows how contribution decreases if Customers C, D, and/or E receive the $16 pricing.

Scenario 2c is the original Scenario #2. The company earned a total contribution of $34 (Cell G9). If all the customers received the $16 price, the total contribution plummets to only $4 (Cell G17).

Whenever a company decides to offer a lower price to some customers via price differentiation, they should run scenarios of varying levels of price cannibalization. They could decide the most likely percent of sales that will have price cannibalization based on the strength of their fences.

Here are some examples of how fences are built.

- The advertising and prices a company offers in one market are not seen by customers in other markets. A stronger fence would be to say that the lower prices are only available for customers or for locations within the first market. A softer fence would allow people to get the discount in other markets if they happened to hear about it.

- Prices that are quoted to a customer are explicitly stated to be only for that customer and not available to other customers. Some quotes or contracts prohibit customers from telling others the price they received.

- Some offers or quotes have very short time expirations.

- Fences may be quoted to everyone with price breaks for volume discounts or for discounts during periods of low usage of the products (e.g., matinee tickets).

- Coupons and rebates may only be mailed to certain customers. They may not be able to be used by others. Rebates that are widely advertised allow customers to decide whether they will actually take the time to submit the rebate for a discount.

Customers and employees must perceive fences as transparent and fair. Customers won’t continue to do business when they perceive the business as unfair. Behavioral finance studies have shown that people won’t transact with another party they see as unfair, even if it’s financially advantageous to them.

Employees won’t enforce fences if they think they’re unfair. It reduces their job satisfaction and increases turnover.

A fence commonly used in banking is the “new money” CD special. This special offers a high rate for bringing funds from other places to the bank. The rate compensates the customer for the time and hassle of moving the funds, especially if it involves the long process of being set up as a new customer.

Staff and customers at banks or credit unions I worked at didn’t always see this fence as fair. Some customers frame their investment in a bank as a relationship, not a transaction. They would question why people who just brought money to the bank should get a better rate than people who have kept their money there for years. Others would contend that all money is the same, so why should new money get a higher rate than any other money?

Some places I worked at would offer new money specials to compensate customers for the higher transaction costs of transferring money. Others wouldn’t offer new money specials for the concerns I just listed. Each company has to decide what’s perceived as fair by customers and employees.

Price Differentiation and Price Structure Examples

Pricing structures help customers make trade-offs between price and value. These structures may simplify the purchase decision, which makes a purchase more likely. Simple structures like bundling or a “good-better-best” product set greatly help most people make purchase decisions.

Let’s face it: not everyone is a CPA or financial analyst who loves to model lots of different options. A CPA, given 24 choices of jam, will break out a spreadsheet to rank each for flavor, sugar content, and compatibility with peanut butter. By the way, blackberry jam is the best, and I have the spreadsheet to prove it.

The Goal of Pricing Structures

Pricing structures try to find the right balance in a transaction between

- Value to the customer

- Price to the customer

- Cost of the product to the vendor

The difference between #1 and #2 is the net economic value to the customer (i.e., the value minus price in the earlier scenarios). The difference between #2 and #3 is the margin to the company. The goal is for both differences to be positive.

Picking a price between the cost of the product and the perceived value to the customer can be broken down into two questions:

- What is the potential price range based on?

- At what level should we set that price?

This lesson on the basics of value-based pricing answers the first question. The second question is based on a company’s pricing strategy relative to the competition and how (or whether) they want to price differentiate amongst their customers. I covered the concepts of price differentiation in the last lesson. I gave a few brief examples, but I will now explore more examples and some potential benefits.

How prices are set can highlight the value provided to the customer. Where there is strong alignment between how the customer is charged and the value they receive, the pricing is understandable and perceived as fair by the customer.

The term “price metric” is often technically used for the units to which the price per unit is applied. Some of these will be examples of this. Some of the examples go beyond this, so I’m using the term pricing structures.

There are an unlimited number of structures or ways to differentiate prices. I’ll list just a few to highlight how they balance value, price, and cost. Also, the lines between these are not sharp, so some have conceptual overlap with others.

Good – Better – Best

“Good-better-best” pricing offers different prices for variations of a product. I noted earlier in the course that customers tend to take the better product at a medium price when given a list of products rated good-better-best or on a price scale of high-medium-low. A high-priced item tends to increase sales of the second-highest-priced item. In other words, the structure of the prices tends to influence product choice.

This pricing structure provides a simple way for customers to choose the price and value trade-off that best works for them. Having only three choices doesn’t overwhelm the customer with too many choices.

Finance and sales staff work together to build three choices that provide value-for-price levels that customers find compelling. Finance makes sure each product variation provides acceptable margins.

Note that the highest level doesn’t need to have a very high margin. It may serve mainly to promote the middle product. The lowest price product may have to be priced with a tight margin to compete with other companies. Thus, the focus on margin would be on the middle product.

Price Differentiation by Customer Segment

Companies often offer different prices to different groups of customers based on the shared needs and value perception of each group.

The value received is perceived by the customer. Benefits and costs that customers don’t value are wasted. Different product variations at different prices provide options to multiple segments whose willingness to pay for value differs.

Sometimes, customers are grouped by their willingness or ability to pay. Two customers may perceive similar value in a product but have a different willingness to pay for the product. Willingness to pay may be as limiting as an ability to pay.

Examples are art performances that give discounts to students and seniors. These groups may not be willing to pay as much. In other words, their decision whether to buy a ticket is much more sensitive to price levels than other groups. Some have money but a lower willingness to pay. Others have a limited ability to pay. Offering these groups a lower price that’s not available to the general public allows the theater to gain additional marginal profit. The lower price attracts additional marginal revenue from segments with a lower willingness to pay. This is especially true when the venue doesn’t expect to sell out from general-priced tickets.

Pricing not only signals value, it signals values. My wife and I are fans of a bakery that gives discounts to veterans and those active in the military. The bakery is located not far from an Air Force base. Veterans as a group have a wide variety of willingness and ability to pay. The pricing discount to a military customer segment signals value to a community that highly respects military service. This increases loyalty to the bakery. The size and tastiness of their goods also expand their customers, especially in the waist.

When I worked in banking, we would run specials in the neighborhoods around a new branch that weren’t advertised in other areas. One reason for the high rates was to compensate non-members for the higher transaction costs of moving their money. This is also a penetration pricing strategy of offering a better trade-off of price and value than competitors to build market share.

If customers who lived near our existing branches heard about the special and wanted it, we would give it to them. This increased the perceived fairness of the price differentiation for both customers and staff. Some companies might say the special price is only available at the new location. When I modeled these new market specials, I would include that price cannibalization or run a sensitivity analysis of varying levels of price cannibalization.

These examples show different ways fences are built around different prices. The prices are unique to a set of product features, geography, or certain customer groups. Customers and society tend to perceive these fences and differentiation as fair.

Volume Discounts or Limits

Many products are sold where the price per product goes down as the number of items ordered increases. This is a great way to match a cost structure that’s part per-order cost and part per-unit cost. The two parts of the cost might be:

- The per-order costs of order processing and shipping

- Each product’s variable product costs

Some sharp-eyed cost accountants may point out that shipping costs are often driven by size and weight; they are not a flat rate per order. One industry that has attempted to charge for size and weight is airlines. Airlines set limits on the size and weight of each bag. Storage capacity is limited, and weight drives gas prices. An airline customer who wants to take more than those limits may need to pay for an extra bag. There have also been discussions about charging heavier or larger customers for two airline seats. Long story short, this idea is a public relations nightmare. We can get too tricky by half when matching pricing to cost drivers.

Some companies provide volume discounts and break out the processing costs as a flat fee. It’s a way to keep lower per-unit costs as an anchor price that’s first shown to a customer when customers are comparing between vendors. Customers may have very different price sensitivities to the per-order costs and the per-product costs. Some customers will search for the lowest prices and have low sensitivity to processing costs.

Amazon Prime is a great example of changing the price metric of processing costs to a membership fee instead of being on each shipment. This reduces the friction and price sensitivity of processing costs. It also made processing costs a sunk cost for individual Amazon purchases. It’s a marginal cost for all other vendors the customer looks at.

In banking, some loan origination fees are a fixed-dollar amount. It takes staff almost the exact same time to process a big loan or a little loan. The interest rate varies with the cost of funding. It’s literally set at a margin above the cost of funds. Large loans sometimes get price breaks.

Activity-based costing (ABC) recognizes that there are different activity categories (e.g., unit, batch, product, customer, and market). These costing systems often develop an average cost per activity that can be used to develop a marginal cost per activity. That marginal cost is used to calculate the marginal profit for the per-order pricing (i.e., shipping and handling) and per-unit costs.

Sometimes, customers receive less favorable pricing for higher volumes. Coupons and specials often have a limit on the number of units eligible for the discount. This caps the low or negative margin on the loss leader while hoping the discount is enough to lure in customers to whom the company can cross-sell more profitable products.

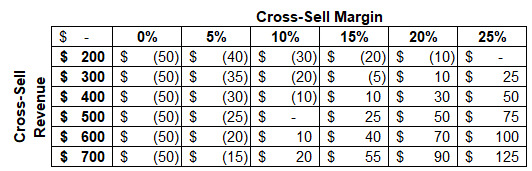

An extreme example of this is a Black Friday special on a product at a very deep discount that’s limited to one unit per customer. In this scenario, the company could run a two-variable table on the cross-sales revenue and margin on that revenue. This sensitivity analysis is important because the customers attracted by the sale may also buy a higher percentage of low-margin items than the store’s average customers.

This table assumes the company is selling a loss leader at a negative $50 net margin. It calculates the total net contribution per customer that comes to the store solely because of the loss leader product. The contribution is calculated across varying amounts of cross-sell revenue and the margin on that revenue. The formula for the net contribution margin is Cross-Sell Revenue X Cross-Sell Margin – $50 Negative Margin from the Loss Leader. Check out my Pricing Profitability Analysis course to learn more about building these two-factor data tables.

By the way, the purchase limit of a special can serve as an anchor that drives up the purchase amounts of the special item. In a study, there was a sale on soup at a supermarket. On some days, there was a sign that read “Limit Twelve,” and on some days, it said “No limit per person.” An average of seven cans were purchased per customer on days that listed the limit of twelve cans. This was twice as much as when there was no limit. In other words, adding a limit increased the number of cans sold.

My favorite example of a volume discount comes from tire stores. Have you ever seen a tire store with a sales pitch that says, “Buy 3 tires and get the 4th free!” Who goes into a tire store to buy only three tires? Of course, many people buy only two tires. For these people, the next two tires are priced like a “buy one, get one free” offer. And so they buy four tires.

Value-Add Services

Value-add services are services that aren’t core to the product but provide a more complete solution to the customer’s needs. They may also be a higher level of service than offered in the standard product.

Many times, a commodity (or highly competitive) product can be paired with services to create value-added bundles that allow higher margins and differentiate the commodity. This can be used to differentiate your products from competitors, but the services are often eventually replicated by competitors. If competitors don’t provide the service or charge for the service, it’s a way to increase the total margin of a transaction.

These services may be what differentiates a “better” or “best” offering from the “good” offering in the good-better-best examples I talked about earlier. For example, software providers may provide higher up-time or faster support response for higher prices.

Another option is to unbundle a current product and service. You then charge pricing that matches the cost to provide each and how customers value each.

Some examples of this type of pricing include:

- A product with free shipping vs. the price for the product and the price for faster shipping.

- One price is for a software license, and a second price is for service levels or maintenance agreements.

These value-add services can be very profitable. In fact, a company may sell the main product at a lower price to capture the sale and then increase the total margin of the transaction by cross-selling the service.

Ironically, many people are tempted to waive the price for value-added services. The costs of services may seem less tangible than the costs of a physical product. Some people may point out that a large portion of service staff are sunk costs. The devastating impact of starting to waive prices for these services is price cannibalization. It becomes harder and harder to charge for these services in the future. Waiving the price may reduce their perceived value by the customer. The costs of the service staff don’t go away, but the revenue for them does. It’s a price war that’s easy to get into. No one wins price wars.

Channel Usage

Some channels are much more expensive to serve customers than other channels. Online banking has much lower average transaction costs than in-branch teller transactions. A software company can likely process email help tickets much more cheaply than telephone calls.

Channel may be so important that it’s not just another way to segment customers. It’s another dimension across which to further segment customer segments. For example, you may charge one set of prices in-store for good, better, and best versions of a physical product and another set of prices for those who buy online.

You can charge for more expensive channels, offer discounts for using less expensive channels, or both. More expensive channels may offer a higher level of value-add services, as l talked about earlier. You may be able to charge for these. Fees are very visible, so you may not be able to charge for them. You might find a value/price trade-off somewhere else if you want to increase profits.

If customers see current services as entitlement, charging for them is seen as unfair. Providing discounts for a cheaper channel is seen as fair and attractive.

A classic example occurred when I was in banking. Banks have had tellers since the beginning of time. Online banking took off in the ‘90s. Adding it was very expensive for banks, especially in the early days. I did the analysis at a regional bank. Marginal revenue was very hard to identify and quantify. Here were the questions we struggled with in the analysis:

- Would being an early adopter attract additional customers, or would this quickly become standard with our competitors?

- Could we charge for online banking to cover the costs?

- Why would we charge for it if the biggest benefit was lowering costs?

- Would we really lower costs because of online banking?

The functionality of early online banking was limited. As time progressed, the value of the channel to customers increased, and the ability to process more transactions at less cost also increased.

Most banks used “carrots” rather than “sticks” to promote online banking versus branch transactions. Banks would waive service charges for customers who switched on electronic statements. Some banks paid a small cash bonus to entice customers to try features like online bill-pay.

Once online banking adoption took off, a few banks were tempted to drive even more transactions out of branches by charging fees for using tellers. Customers revolted. These banks received very bad press.

Finance can calculate the cost savings of a customer switching channels to help determine the discount to offer customers. Once again, the starting point might be the per-transaction cost from an activity-based costing system. However, this is an area where average costs may be very different than marginal cost savings.

In these analyses, the marginal cost is the discount offered to customers to switch channels. This should be offset by the marginal cost savings. These must be true reductions of costs, not just reductions of transactions times an average cost.

Banks have paid huge amounts of money for online banking, mobile banking, and other technology. My guess is that you haven’t seen much of a decrease in tellers at your local banks. In my online banking analysis, I could easily measure costs, but I couldn’t identify true cost savings.

Some banks adopted these technologies defensively as an increased cost of doing business. If we didn’t offer the new technology, we would lose customers. The cost of the technology was less than the lost customer profitability.

Smart banks found the solution in channel redeployment. Basic transactions shifted online. Computers can process transactions faster and with more accuracy than tellers. Tellers were retrained as sales staff. They spend more time getting to know a customer’s financial needs and how the bank can meet those needs. This leads to increased cross-selling and profits. The ultimate benefit turned out to be additional revenue from existing products, not cost savings by reducing existing staff.

Bundling

A bundled product offers one price for a group of products the customer can buy individually. A key to its effectiveness is that the price is less than the sum of the prices of its parts.

Every customer has a different value that they place a product. When you quote prices to each person, you can try to find the price and value match for each customer. It’s much harder to do that with prices that are listed for all to see. Bundles allow pricing to capture the value of a group of products by people who value the components differently. It can cause people to buy more than they were planning.

Anyone who has been to fast food restaurants has been presented with a “meal” or “combo.” It makes ordering components of a meal easier, even if we buy components in a bundle we wouldn’t have bought if we were deciding which components to buy individually.

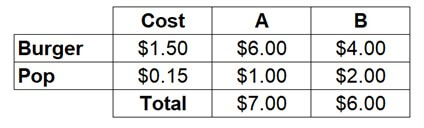

Let’s look at a simple fast-food bundle.

A burger costs the restaurant $1.50 to make, and a pop costs $.15. Let’s first stop and acknowledge our cultural differences. In the northwestern United States, we say “pop.” Feel free to replace the word “pop” with whatever word your part of the world uses for highly sweetened carbonated water.

Customer A values the burger at $6 and the pop at $1. Customer B values the burger at $4 and the pop at $2. If the restaurant charges $5 for a burger and $1.50 for a pop, customer A will buy a burger. Customer B will buy a pop. The restaurant earns $6.50 of revenue at a cost of $1.65 for a net contribution of $4.85.

The owner of the restaurant then takes this course and decides to offer a combo meal of the burger and pop for a price of $5.50. Both customers now buy the combo. The restaurant earns $11 of revenue at a cost of $3.30 for a net contribution of $7.70. Everybody is fat and happy!

Bundling is an easy way for a company to price a combination of products to provide value to customers and provide good margins to the company. It’s a low-cost way to cross-sell. It is especially effective for products with low marginal costs. The increased sales offset the decreased margin of the individual items. Bundling may also improve customer satisfaction and loyalty.

Bundling allows differentiation. Competitors may have products similar to some of your products but are less likely to match your bundled product exactly. It’s more work for customers to compare value and price between products when the products are different.

An anchor number customers may use for value is the sum of the prices of the products in the bundle. A company can facilitate this by adding the prices of all the components together. They then compare that high amount to the lower bundled price. It’s a proxy for the value the customer receives.

Capped Revenue Pricing with Variable Cost Structures

Another type of bundling is to offer memberships, subscriptions, or all-access passes instead of buying items individually. I’ll use the word “pass” to encompass all three types of bundles.

Many continuing professional education (CPE) course sites offer individual courses and passes that sell at a large discount to the individual courses. A customer may be willing to pay a very high price for a few courses offered by the site but be willing to pay much less for the other courses. In addition, CPAs need a certain number of courses each year.

The pass gives them the high-value courses they want plus the other courses they need, all at a low marginal price. This type of bundle works well when you have a very low marginal cost of delivery and/or a revenue split with your content suppliers.

What happens if a company is at risk of some “super-users” who drive the cost to serve them above the bundle price? Overage fees are a common way to deal with this. Utilities use these. Each customer gets a certain amount of water for a flat rate. Any water over that is charged by usage. This adds a metering cost to the company for all customers and more expensive accounting. You must decide your risk of “super-users” versus these costs.

Value Sharing

I mentioned that one way for membership sites to maintain margins is a revenue share. A value share is a similar idea in which customer cost savings or cash increases are split with the vendor. This reduces the risk to the customer but shifts the risk to the vendor. The hope is that this risk shift will drive additional sales. Vendors have to develop a clear and enforceable split calculation and develop probabilities and magnitudes of their split.

A classic example of this is a contingency-fee lawyer. Some consulting companies bill this way.

Sometimes, it’s hard to quantify the dollar amount of value received by the customer. In those cases, a proxy performance metric may be used as the basis for calculating the customer’s payment to the vendor. For example, increased sales by the customer could reasonably be attributed to the work of the vendor and be used as a basis for a percentage split to the vendor.

All the examples in this lesson show ways to allocate and increase value between companies and customers. To maintain good margins, companies must match their cost structures to pricing structures. Sales and accounting can work together to find the best way to provide value to customers, identify pricing structures and levels, and calculate costs to arrive at acceptable profits for the company.

For more info, check out these topics pages: